Back in 2004, when the massive Indian Ocean earthquakes and subsequent tsunami hit Indonesia, India, Sri Lanka and Thailand, many people were saved when they clung on to mangrove trees in shoreline forests. Now, experts look at other benefits these forests bring.

The natural disaster that struck these nations killed a grand total of 230,000 residents, but authorities estimate that the number could have been a lot larger. Seaside forests were identified as one of the factors that helped save lives.

In addition to that, the mangroves can help safeguard property and beaches during hurricanes, tsunamis and floods, by calming down the waters, and acting as a natural barrier in their path.

US Geological Survey (USGS) land change scientist Chandra Giri took it upon himself to analyze how the mangrove forests become so valuable in case of extreme natural events.

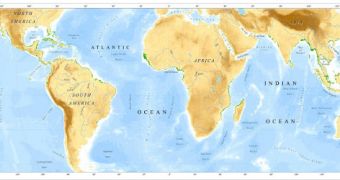

But the researcher hit a snag along the way, when he attempted to quantify this effect. So he took another path to conducting the work. Together with an international team of colleagues, he began developing the first high-resolution, satellite-based global map of mangrove forests.

When the datasets were finally published in the Journal of Global Ecology and Biogeography, earlier this year, the international scientific community was puzzled to learn that mangrove forests are occupying a very small part of Earth's surface.

This is a very bad situation, biologists say, because these forests are treasure troves for biodiversity. They can foster the development of multiple species, that live together in intricate and carefully-balanced ecosystems.

As soon as exterior influences are introduced in the mix, that fragile balance can be broken. This is why strong conservation efforts are needed worldwide to protect these forests, and the habitats they contain.

“We knew that mangroves are extremely precious as a robust habitat, refuge and food source for hundreds of wildlife species as well as for humans,” Giri tells NASA in an interview.

“And they store a disproportionately greater amount of terrestrial carbon than a lot of other ecosystems. They’re clearly an important ecosystem when it comes to biodiversity. But no one has systematically assessed the forests as disaster protection with hard data at a broader scale,” the expert adds.

The recently published maps show precisely how many mangrove forests there are in the world, and where each of them is located. The largest density can be found in Asia.

“We know the Asia-Pacific region, Indonesia in particular, has the most mangrove forests. From UN and other reports, we also know Asia is the region most at risk from deadly natural disasters like the tsunami,” Giri explains.

“So, we’re better positioned to investigate mangroves’ value as armor against them, and to help substantiate conservation efforts in the region to stem the forests’ decline,” he concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //