Investigators finally discovered the central switch that causes healthy brain cells to be converted into diseases, epileptic ones. The finding could provide a new target for future treatments, that would prevent the development of the disease in the first place.

The work, carried out by researchers in the United States and France, should be useful for both treating and preventing temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE). If this research materializes into concrete therapies, then it could help between 1 and 2 percent of the world's population.

TLE is the most common form of epilepsy in adults, and the second most common neurological affliction. The only condition more prevalent in the adult population is migraine headache. Some 30 percent of all temporal lobe epilepsy patients are unresponsive to conventional treatment methods.

French scientists, led by Christophe Bernard of the University of Marseille and Inserm, worked closely with colleagues at the University of California in Irvine (UCI), who were led by Dr. Tallie Z. Baram.

“This discovery marks a dramatic change in our understanding of how TLE comes about. Previously, it was believed that neurons died after damaging events and that the remaining neurons reorganized with abnormal connections,” says Baram, who is the UCI Danette Shepard Chair in Neurological Studies.

“However, in both people and model animals, epilepsy can arise without the apparent death of brain cells. The neurons simply seem to behave in a very abnormal way,” adds the expert, who is also a neurologist and neuroscientist at the university.

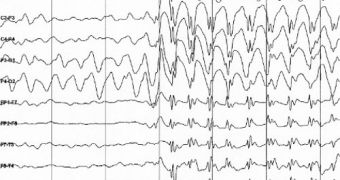

He explains that TLE occurs when the molecules governing the behavior of brain cells called neurons undergo a major reorganization. This event may be prompted by traumas, brain infections, of may even be triggered by prolonged febrile seizures.

The ion channel HCN1 was found to play an important role in governing the development of epilepsy. It was found that the gene controlling this channel, alongside 36 other genes, are severely altered by TLE-triggering events. The repressor protein NRSF was found to be responsible for these changes.

“NRSF operates like a master switch on many genes affecting neuron function. And if its levels increase, it can provoke changes lasting for years,” UCI researcher and study coauthor Shawn McClelland says.

Details of the new study appear in the latest online issue of the esteemed journal Annals of Neurology.

“We’re quite excited about this discovery. Understanding how previous brain infections, seizures or injuries can interact with the cellular machinery to cause epilepsy is a crucial step toward designing drugs to prevent the process,” Baram concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //