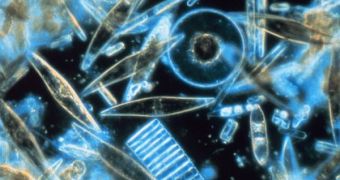

Diatoms represent one of the most important groups of eukaryotic algae and they are mostly unicellular phytoplankton. The organisms, which live in the world's seas and oceans, are responsible for producing about 25 percent of the total amounts of oxygen in the world, yet little is known about their very structure. One of the things that fascinated and puzzled researchers was how exactly their glass-like skeleton formed. A part of this mystery has recently been solved, when investigators have uncovered how silica, the main constituent of glass, is moved around in the small organisms, AlphaGalileo reports.

According to a new scientific paper, appearing in the latest issue of the respected open-access journal PLoS One, the genes that are responsible for storing and moving silica around usually reorganize themselves in the presence of the compound, which facilitates the formation of the shells. In charge of the investigation have been scientists from the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and the ENS Paris, in France. The experts say that the new knowledge could help scientists forecast possible issues related to the health of the diatoms, brought forth by variations in the natural silicon and carbon cycles.

“Elucidation at the molecular level of silicon biomineralization is essential if we are to predict the effects of anthropogenic environmental changes on the biogeochemical cycle of silicon,” CNRS expert Pascal Jean Lopez says. He has been the leader of the research team behind the new study. Considering that the diatoms produce about as much oxygen as the rain forests, it stands to reason that more studies are conducted to understand how they function.

Additionally, the diatoms are also used as a modeling tool in the field of nanotechnology research, and they provide a clear indication of the factors affecting the environment. Their health also provides climatologists with clues that the natural silicon or carbon cycles are out of balance. If the diatom counts are too high or to low, then they know that something is out of balance. In the new study, a single species of diatoms, Phaeodactylum tricornutum, was analyzed.

The scientists chose it because its members did not necessarily have to develop glass-like exoskeletons, but some did so, nonetheless. The team managed to identify a number of genes inside the organisms, which either played a role in the cell's sensitivity to the diluted form of silicon – silicic acid –, or were involved in the capture, storage and processing of the compound, which was then used for the shells.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //