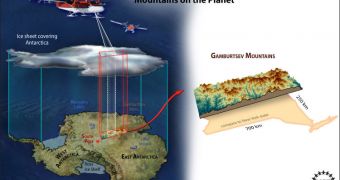

A group of researchers from Australia, Canada, China, Germany, Japan, the United Kingdom and the United States was recently able to determine how a mountain chain buried under miles of ice underneath Antarctica formed.

This has been a mystery for investigators for about 53 years, since the subglacial mountains were first discovered. The US National Science Foundation (NSF) funded the study, and also acted as the coordinator of the American component of the mission.

A scientific expedition was deployed to this mysterious mountain range between 2007 and 2009, as part of the International Polar Year (IPY). More than 60 researchers participated in the effort, and they determined that no single tectonic event formed the mountain range.

Instead, it would now appear that several, successive earthquakes led to the formation of the impressive subglacial mountain chain. Details of the investigation were published in this week's issue of the top scientific journal Nature.

The Gamburtsev mountains are located underneath the East Antarctic Ice Sheet (EAIS), at a location where the massive ice fields now covering the Southern Continent are believed to have originated.

“Resolving the contradiction of the Gamburtsev high elevation and youthful Alpine topography but location on the East Antarctic craton by piecing together the billion year history of the region was exciting and challenging,” investigator Carol Finn explains.

“We are accustomed to thinking that mountain building relates to a single tectonic event, rather than sequences of events. The lesson we learned about multiple events forming the Gamburtsevs may inform studies of the history of other mountain belts,” he goes on to say.

“The youthful look of any mountain range may mask a hidden past,” adds Finn, a researcher with the US Geological Survey (USGS), and one of the coauthors of the new Nature paper. The next step the team plans to take is to analyze material collected from the mountain range itself.

However, that is bound to be extremely difficult, since miles of ice cover the tips of the mountains. Drilling is the only possible way to go about collecting the required material, explains Columbia University Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory expert Robin Bell.

“We have samples of the moon, but none of the Gamburtsevs. With these rock samples we will be able to constrain when this ancient piece of crust was rejuvenated and grew to a magnificent mountain range,” she concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //