Investigators at the American space agency say that studies conducted thus far on comet Hartley-2 indicate that the celestial body is part of a new class of objects that has never been analyzed before.

After the NASA EPOXI mission flew past the comet recently, experts got a fairly in-depth view of what was going on underneath its surface. What they saw was unexpected – the object's core was not at all uniform, as studies had predicted.

Previous works had suggested that a remnant or remnants of the early solar system lie at the core of each comet. Gaining a better understanding of such structures, if they truly exist, is extremely important since that may in turn provide a better understanding of the early solar system.

Another thing that researchers were worrying about was whether comets are put together from mini-comets that assemble themselves, or if they are created as thin tendrils of dust and ice gets drawn slowly inwards, therefore producing a uniform mass.

While experts were expecting Hartley-2 to clear out this mystery, this did not happen. “We haven't seen a comet like this before. Hartley-2 could be the first of a new breed,” explains Michael Mumma.

The expert, who is based at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC), in Greenbelt, Maryland, was the leader of the research team that analyzed the EPOXI data. The work revealed that the comet did not have an uniform core.

“We have evidence of two different kinds of ice in the core, possibly three. But we can also see that the comet's overall composition is very consistent. So, something subtle is happening. We're not sure what that is,” Mumma explains.

Details of the new investigation appear in the May 16 special issue of the esteemed publication Astrophysical Journal Letters. Experts from the California Institute of Technology and the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research were also a part of the work.

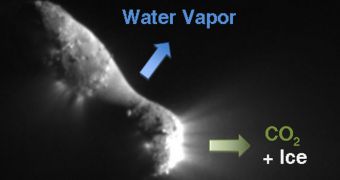

“The carbon dioxide gas drags with it chunks of ice, which later evaporate to provide much of the water vapor in the coma,” explains the head of the EPOXI science team, Michael A'Hearn.

“In other comets that have been visited, most of the water appears to be converted into gas below or at the surface. We have not seen icy grains, or at least, very few, being dragged into the coma,” adds the expert, who is based at the University of Maryland.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //