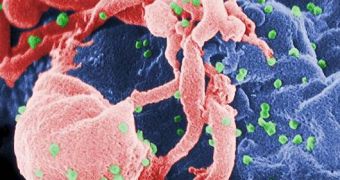

HIV has remained impervious to advancements in medicine over the last 25 years, and all the research paths explored by scientists seem to dead-end at some point. The current approach is to engineer super-molecules made from compounds found outside the human body, and to make them face the virus head-on. A new method of fighting the disease, detailed in the March 15th issue of the journal Nature, could involve boosting and accelerating the natural human immune response to foreign invaders.

In so-called “slow-progressing” patients, physicians have identified an unusual “team” of naturally-occurring antibodies, which seems to hamper the development of AIDS more effectively than even the most advanced artificial drugs.

That's why Rockefeller University (RU) scientists led by Sherman Fairchild professor Michel C. Nussenzweig, the head of the Laboratory of Molecular Immunology, believe that the best new approach to the disease would be to bombard the virus with cocktails of natural antibodies, rather than focus on a single magic cure.

This new method is called the “shotgun approach,” as opposed to the previous “bullet approach,” where the bullet stood for a single substance being introduced into the body to fight HIV, engineered from scratch in the lab. But the previous method proved to be nearly impossible to apply in real life, on account of the fact that even the substances in the vaccine were foreign to the body.

“We wanted to try something different, so we tried to reproduce what's in the patient. And what's in the patient is many different antibodies that individually have limited neutralizing abilities, but together are quite powerful. This should make people think about what an effective vaccine should look like,” Nussenzweig, who is an investigator at the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, adds.

Despite the fact that HIV mutates incredibly fast in the human body, its only weak point remains common to all the new strains, and that is the gp140 protein, which the virus requires in order to infect immune cells. Four antibodies engineered in the lab have proven efficient in inhibiting the action of HIV in cultures, but the four could not be produced in the human body naturally, so the entire endeavor has failed. “Individually, they're not as strong as the Famous Four,” Nussenzweig underlines in talking about the new types of antibodies that his team advocates to be using.

The natural antibodies in the human immune system are also able to distinguish between a number of HIV strains, although admittedly they cannot recognize all of them. Still, their abilities could be artificially augmented, and all AIDS sufferers could be turned into “slow-progressing” cases, or even cured, despite the fact that the effort would take quite a long time to complete.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //