HIV is bad, but combined with any other disease, it's worse.

A team at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine has showed that the use of entecavir, an antiretroviral drug widely used against hepatitis B infections, in patients co-infected with HIV leads to cross-resistance to other antiviral chemical in the treatment against HIV.

"Our results show that entecavir is no different from any other that has been shown to be active against HIV - it breeds resistance rapidly, despite its ability to reduce the amount of HIV in the body," said senior study author and infectious disease specialist Dr. Chloe Thio.

Worldwide, more than 4 million people are believed to be infected with both viruses.

"The alert should go out to co-infected people to consult with their physicians immediately about entecavir to see if it is the right drug to treat their hepatitis B in the first place and to evaluate alternative therapies," said Thio, an associate professor of medicine at Johns Hopkins.

"The good news is that co-infected patients already on HIV therapy can still use entecavir to treat their hepatitis B, but the bad news is that there are now fewer options for treating hepatitis B first," she adds.

Hepatitis B virus infects the liver, inflicting cirrhosis, liver cancer and if untreated, can lead to death from liver failure in a quarter of the patients.

Entecavir was launched on the market in March 2005 and is a leading treatment for chronic forms of hepatitis B.

Lab and clinical investigations revealed that within six months of entecavir therapy, the M184V mutation of HIV emerges.

"Viruses with this mutation are known to be resistant to lamivudine, better known as 3TC, a medication that prevents HIV replication and is a cornerstone of most drug-combination therapies used to fight the immune system disease," said Thio.

"Because lamivudine is in the same category of HIV therapies as another widely used drug, emtricitabine, its effectiveness is also compromised by entecavir," she said.

Entecavir's was reported to have an anti-HIV activity in three co-infected patients, with a tenfold decrease in the amount of HIV in their blood.

Lab results showed that entecavir, in concentrations less than a tenth of what is used in humans, cut the number of newly infected cells with HIV in half.

But, at increasing concentrations, entecavir did not present greater impact on suppressing HIV replication.

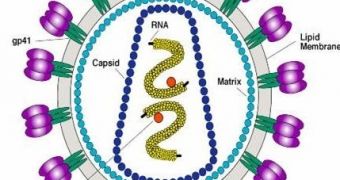

HIV is well known for its ability to shift form, developing resistance to therapies designed to stop its action.

Similar experiments with entecavir, immune cells and the M184V form of HIV revealed that the drug did not impede the virus from infecting the cells.

"This provided evidence that the drug specifically fostered development of this mutation in HIV, later confirmed by clinical testing."

In one of the co-infected patients, tested revealed no sign of the M184V mutation's existence before taking entecavir, but after four months of entecavir therapy, the mutation was present in 61 % of viral samples, and 96 % at six months.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //