Tests conducted on blind patients brought hope to the scientific community, when new-generation retinal implants proved to be extremely effective in returning at least partial sight to patients who could not see at all. The test participants were able to recognize large objects and obstacles, and one of them was also able to read large print. After decades of slow and wrenching progress, the innovation finally provides an effective treatment to blindness, experts say. The good news is that the new implants may be made available within only a couple of years, Technology Review reports.

Retinitis pigmentosa and age-related macular degeneration are two of the conditions that the new retinal implants address best. These devices need to replace the functions that photoreceptor cells at the back of the eye – the retina – usually perform. They essentially have to convert light entering the eyes into electrical signals that are then sent via the optical nerve to the visual cortex, where they are processed and turned into the visual sensation.

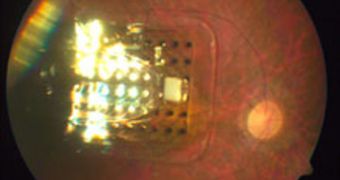

The implants are, in fact, made of electrode arrays, which are inserted either below or above the retina. They emit electrical impulses that stimulate the rest of the visual circuitry remaining in the eye. The signals are then picked up by the optical nerve and taken to the brain. The end-result is a pixel-like sensation, where the patient perceives a large object, for instance, as a number of pixels stacked on top of each other, in a specific pattern. The pixels of light that appear in the visual field are called phosphenes, experts say.

Over the past few years, numerous claims about the results of retinal implants have been made, but with little proof in the background. The Chair of the Artificial Vision symposium, held last week in Bonn, Germany, says that the new results are drawn from several independent projects that were presented at the meeting. University Eye Clinic in Aachen expert Peter Walter also adds that a number of long-term studies has already been conducted, which seems to validate the efficiency of the new methods. “Within two or three years we could have products available,” he believes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //