Google has revealed that Facebook and its own services are among the most affected by the European “Right to be forgotten.”

According to the world’s largest Internet company, since the court decision was handed back in May, more than 3,300 links to material on Facebook has been removed, which is 1.9 percent of the 169,500 links to websites that Google has removed from its search results.

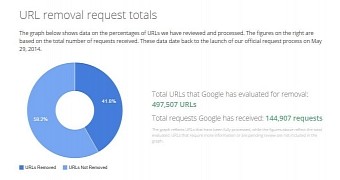

There have been over 142,000 requests to remove links to over 490,000 web pages from Google Search results, the company reveals, mentioning that this has happened since May 29 when its form went live. Previous to this date, there have been other demands sent into the company that are not mentioned this time around.

“We believe it’s important to be transparent about how much information we’re removing from search results while being respectful of individuals who have made requests. Releasing this information to the public helps hold us accountable for our process and implementation,” states the company’s Jess Hemerly, public policy manager at Google.

The most removal requests the company has received come from France, Germany, the United Kingdom, Spain and Italy. Among the top 10 domains that the URLs come from are Facebook, Badoo, as well as two Google-owned and operated sites, namely YouTube and Google Groups, both of which have their own mechanisms to request removal of content directly from the platform.

Even though Google has been swamped with demands, the company has only decided to remove the URLs in 41.8 percent of the cases, while in the rest of 58.2 percent they decided against it. The numbers vary from country to country, but there are few countries where the number of URLs removed is bigger than the ones of those ignored.

What Google has to deal with

“To give you an idea of the range of requests we’ve received and the kinds of decisions we’ve had to make, we’ve included some examples of real requests we’ve received from individuals. These are anonymised so that they don’t include information that would identify individuals,” Hemerly writes.

As promised, Google included some examples. While names were not offered, some of these cases are ridiculous. A woman from Italy, for instance, requested to have Google remove a decades-old article about her husband’s murder, which included her name, which Google agreed to.

On the other hand, a financial professional from Switzerland decided to ignore Google’s clear warning that it won’t help people erase their criminal pasts. The man wanted for the company to remove more than ten links to pages reporting on his arrest and conviction for financial crimes, which Google said no to.

Another individual from the United Kingdom wanted to have Google vanish some links referencing to his dismissal for sexual crimes committed on the job. The Internet giant refused. A doctor from the same country wanted Google to remove over 50 links to newspaper articles about a botched procedure.

“Three pages that contained personal information about the doctor but did not mention the procedure have been removed from search results for his name. The rest of the links to reports on the incident remain in search results,” the company explains.

Another individual, a former clergyman, wanted Google to remove links to two articles covering an investigation of sexual abuse accusations while in his professional capacity, which Google also rejected.

All in all, by including these details into its Transparency Report, Google is giving us all a preview to what it has to do to comply with the European decision. Since there’s no automated system set in place, the company has to make all these decisions individually, which is highly subjective.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //