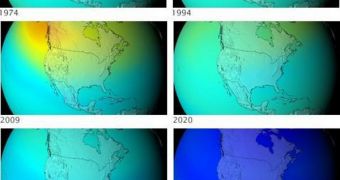

Researchers have recently determined that one of the factors promoting global warming today is the healing of the ozone layers. Its effects are most dominantly felt in the Southern Hemisphere, as the hole first formed over Antarctica. The original damage was done through the excessive use of chlorofluorocarbons (CFC), chemicals that endured in the atmosphere, and prevented ozone from being replenished and protecting our planet from dangerous ultraviolet (UV) rays from the Sun.

In the new investigation it became apparent that, while the ozone layer indeed let UV radiation slip through, it also generated a feedback mechanism of sorts, which protected the areas underneath from excessive warming. A direct consequence of the hole were higher speed winds, which in turn promoted the formation of larger amounts of high-altitude clouds above Antarctica. These clouds were directly responsible for reflecting a lot of sunlight back into space, protecting the Southern continent from being warmed up, and melting.

“These clouds have acted like a mirror to the Sun's rays, reflecting the Sun's heat away from the surface to the extent that warming from rising carbon emissions has effectively been canceled out in this region during the summertime. If, as seems likely, these winds die down, rising CO2 emissions could then cause the warming of the southern hemisphere to accelerate, which would have an impact on future climate predictions,” the coauthor of the investigation, University of Leeds Professor Ken Carslaw, explains. Details of this work will appear tomorrow, in the January 26 issue of the respected scientific journal Geophysical Research Letters.

As the hole is currently beginning to heal, thanks to international agreements banning the use of CFC, the amount of clouds that form underneath could decrease, or the clouds themselves could become less bright and reflective. This would translate into an accelerating global effect in Antarctica, which could result in global sea-level rises. “Our research highlights the value of today's state-of-the-art models and long-term datasets that enable such unexpected and complex climate feedbacks to be detected and accounted for in our future predictions,” Carlsaw reports.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //