A group of investigators in Europe propose in a new study that mammoths may have not been the majestic, healthy and strong creatures that we have come to envision them as. According to some evidence the team has recently uncovered, it would seem that inbreeding was a common habit among these creatures, which eventually led to a lack of genetic diversity, and to numerous mutations.

The research was led by paleontologist Jelle Reumer, from the Natural History Museum Rotterdam, and Frietson Galis, a paleontologist with the Naturalis Biodiversity Center in Leiden, both in the Netherlands. The joint team investigated mammoth bones that have been dredged from the bottom of the North Sea over the past few years.

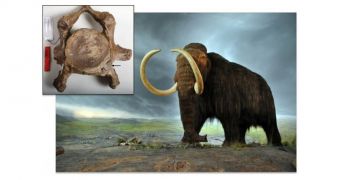

Investigators paid close attention to discovering rib facets on mammoth neck bones, and were able to identify these structures in 3 out of 9 cases. All samples were borrowed from local museum collections. The picture that emerges from this research is one where the image of the 3-meter (10-foot), 6-ton mammoth starts to deviate from reality.

Most likely, the animals were genetically deformed, wobbling through their environments while using just a small percentage of their original capabilities. Extreme pressure from their changing habitats, hunts by humans, and genetic anomalies were probably the factors that eventually led to their demise, no more than 10,000 years ago, Science Mag reports.

While these contributing factors were well known, scientists had no idea that inbreeding also played a role in their extinction. Reumer and Galis discovered an interesting structure in one of the fossilized bones recovered from the North Sea, a round and flat area on a large neck vertebra bone. This suggests the presence of a small rib, called a cervical rib, attached to this particular neck bone.

Instances of such malformations can be observed in humans, too. In 90 percent of all cases of people born with a cervical rib, death occurs before adulthood. In mammoths, the team suspects that the extra rib occurred as a result of both environmental conditions – including famine and stress – and inbreeding. Establishing the proportions to which each event contributed is nearly impossible.

“Cervical ribs indicate there has been a disturbance of early pregnancy,” Galis explains, adding that chromosome abnormalities and cancer can also play a role in the development of such structures. The fact that these structures were discovered in 33 percent of analyzed samples indicates a widespread problem among ancient mammoths.

“This seemed [to be] an extremely high incidence” of cervical ribs in the general mammoth population, Reumer adds. When comparing these results with those obtained from a search of cervical ribs in modern-day elephant populations, scientists have found that only 1 in 21 individuals in existing pachyderm species develops this condition.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //