A group of astronomers in Japan have recently used the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) telescope in Chile to conduct a series of interesting observations of the nearby star HD 142527, which is located just 450 light-years from Earth.

The team was able to discover a gas giant that is forming surprisingly far away from its parent star. What is equally-interesting is the fact that the star may not yet be fully formed itself. This is the first time astronomers have identified such a weird arrangement in a young star system.

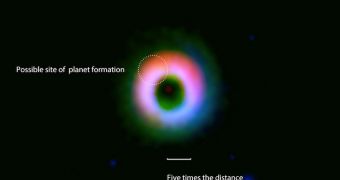

According to ALMA data, HD 142527 is surrounded by a giant gas and dust ring, a feature also known as a protoplanetary ring. What is weird about this particular structure is that it lies very far away from the star, at a distance of roughly 5 astronomical units, or five times the Sun-Earth distance.

Earlier ALMA observations have revealed that the star on which this system is centered is only 2 million years old. By comparison, the Sun is around 4.6 billion years old. Astronomers took advantage of this radio telescope's amazing capabilities to image the clouds of matter that fuel both the star and its protoplanetary ring in exquisite detail.

Images of the system reveal a brightening in the northern parts of the disk, suggesting that an accretion nucleus may exist at this location, around which at least one gas giant-class extrasolar planet may be forming. Making this discovery would have been impossible with optical telescopes, because the entire area is smothered in gas and dust.

The emissions recorded from the northern sector of the disk are roughly 30 times brighter than those from the south side, says Osaka University assistant professor of astronomy Misato Fukagawa.

“I have never seen such a bright knot in such a distant position. This strong submillimeter emission can be interpreted as an indication that large amount of material is accumulated in this position. When a sufficient amount of material is accumulated, planets or comets can be formed here,” the expert adds.

Details of the new study appear in a paper posted to the preprint server arXiv. The authors write that studying this particular star “offers a rare opportunity for us to directly observe the critical moment of planet formation and can provide new insights into the origin of wide-orbit planetary bodies.”

“HD 142527 is a peculiar object, as far as our limited knowledge goes. Our final goal is to reveal the major physical process which controls the formation of planets. To achieve this goal, it is important to obtain a comprehensive view of the planet formation through observations of many protoplanetary disks,” concludes Fukagawa, quoted by Space.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //