Officials from the European Space Agency (ESA) say that the Gravity Field and Steady-State Ocean Circulation Explorer (GOCE) mission has provided, in addition to extremely-accurate readings of Earth's gravitational pull, an interesting new model on which to build more advanced spacecraft.

According to scientists, GOCE is one of the most remarkable satellites ever built, in terms of the type of studies it conducts, the altitude at which it flies, the propulsion system it uses, and how all these aspects, and many more, come together in a single vehicle.

The satellite was launched to space aboard a Rockot delivery system, from the Plesetsk Cosmodrome, in northern Russia. Takeoff occurred at 14:21 UTC, on March 17, 2009, and the purpose of the mission was to collect enough gravity data to create the perfect geoid.

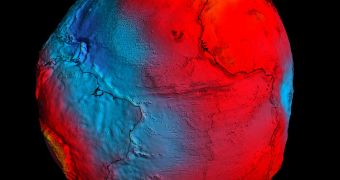

The geoid is a term that refers to the theoretical surface of equal gravitational potential on Earth. Basically, it's what our planet would look like if all areas had the same gravitational pull, not taking into accounts mountains and oceans.

In order to establish the geoid, GOCE had to be outfitted with an extremely sensitive gravity gradiometer, which needed to fly at an altitude of just 270 kilometers (167.7 miles) in order to produce the accurate results scientists were interested in.

But this presented researchers with a problem, since most low-Earth orbit (LEO) satellite fly at altitudes above 400 kilometers (248.5 miles). Below this levels, atmospheric drag is too high, slowing down spacecraft and forcing them to reenter the atmosphere.

This issue was solved by employing an innovative electric ion engine, which is able to compensate for this decay, and maintain the satellite steady. Over the course of three years of operations, this approach has proven its efficiency.

Now, after the geoid has long since been compiled, experts from the Delft University, in the Netherlands, are trying to develop a method of studying air density and wind in space, by cross-referencing data from the satellite's accelerometer with its electric ion engine activation patterns.

Data extracted from this study will be of extreme use for establishing propellant budgets, optimizing mission orbits, planning reentry operations and avoiding collisions with space debris, for upcoming orbital missions.

“The GOCE density measurements are lower than those predicted by models. This is in line with the results of other recent investigations, which suggest that the upper atmosphere has been cooling and contracting over the last decades,” an ESA press release explains.

“There was an additional drop in temperature and density around the time GOCE was launched. The causes of these drops are only partly understood. However, GOCE has benefited from the current environment, using far less propellant than predicted,” the statement concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //