Physicists from the Rice University managed to develop a new method for producing the two-dimensional sheet of carbon atoms known as graphene, which involves the use of sugar and related, carbon-based molecules. The graphene produced in this manner is nearly perfect.

This carbon compound is currently being touted as one of the materials on which humankind could build a better future for itself. It was only discovered in 2005, but its creators have already won the 2010 Noble Prize in Physics for their achievement.

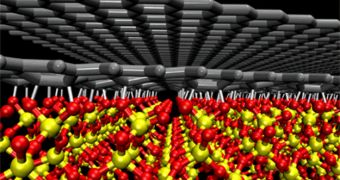

At this point, the material is being researched around the world, and scientists are continuously working on improving production methods associated with synthesizing the stuff. Graphene has a hexagonal, honeycomb-like structure.

It is made up exclusively of carbon atoms, and this grants it some special physical and chemical abilities, such as the capability to conduct electricity just as efficiently as copper. This material is however significantly stronger, and can be modified in a variety of manners by adding various chemicals to it.

What is really remarkable about the approach the Rice team took to synthesizing graphene is the fact the process works with molecules that are easy to find, and that the material is created in a single step.

If adopted, the method is bound to bring graphene production capabilities into everyday life, enabling a wide array of research groups and companies to create their own graphene to use, or run studies on. This could indirectly contribute to breaking through with research in this field.

The work was carried out in the lab of Rice chemist James Tour, who explains that the new way of producing graphene works at just 800 degrees Celsius, as opposed to the 1,000 degrees needed in other approaches.

While this variation may seem insignificant at first, physicists say that it makes a world of difference.“At 800 degrees, the underlying silicon remains active for electronics, whereas at 1,000 degrees, it loses its critical dopants,” Tour says.

The expert holds an appointment as the Rice T.T. and W.F. Chao Chair in Chemistry. He is also a professor of mechanical engineering and materials science and of computer science at the university Tour also authored a research paper detailing the findings, which appears in the latest online issue of the top journal Nature.

“Each day, the growth of graphene on silicon is approaching industrial-level readiness, and this work takes it an important step further,” Tour explains. He says that funds for the study came from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research and the Office of Naval Research.

During the investigation, graduate student Zhengzong Sun determined that placing carbon-rich sources such as sugar on substrates made out of nickel and copper resulted in the formations of layers of graphene whose traits could be controlled.

Zheng Yan, Elvira Beitler and Jun Yao, all graduate students at Rice, and postdoctoral research associate Yu Zhu, were involved in the investigation as well.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //