Experts propose that the efficiency of implants aimed at restoring vision in the blind could be considerably augmented by the use of systems that strengthen the connection between the implant and the healthy neural cells at the back of the eye.

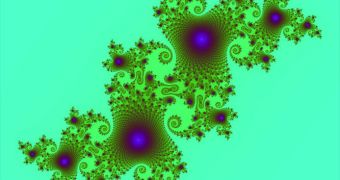

This could conceivably be attained using tiny clusters of a special material that is capable of self-assembling into fractal-like structures in the eye. This would enable the implants to adapt themselves better to the unique structure of the human eye.

Eye implants work only on people who are blind due to conditions that do not affect the nerve cells at the back of the eye. In other words, if there is something wrong with the light receptor cells on the retina, then this can be handled.

What an implant does is it bypasses the receptor cells, and binds artificial, light-processing cells with the neural fibers. This allows the transmission of electrical impulses to the area of the cortex that processes visual stimuli without the use of retinal cells.

One of the reasons why cameras and eye neurons are currently incompatible in many areas is because neurons follow a fractal-like, branching path, whereas the electronic diodes used to capture light in artificial implants follow a straightforward one.

University of Oregon physics professor Richard Taylor says that the efficiency of retinal implants could be improved considerably by adding small clumps of materials inside the photodiodes used to capture light and convert it into electrical signals.

These fractal-enhanced devices would transmit their information a lot more efficiently to the eye, potentially allowing patients to see in even more detail than currently possible. The Oregon team says that the new system would allow nearly-full data transmission.

“Remarkably, implants based purely on camera designs might allow blind people to see, but they might only see a world devoid of stress-reducing beauty,” Taylor writes in a statement released by the university.

“This flaw emphasizes the subtleties of the human visual system and the potential downfalls of adopting, rather than adapting, camera technology for eyes,” he concludes, quoted by PopSci.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //