On Saturday, January 14, the High Frequency Instrument (HFI) aboard the European Space Agency's (ESA) Planck spacecraft ran out of its absolutely-essential coolant. While this marks the end of HFI's operating life, it also marks the completion of the first survey of residual light from the Big Bang.

After the Universe rapidly expanded into being, some 13.75 billion years ago, it spent the first 400 million years or so at tremendously high temperatures and pressures, expanding constantly and at an accelerated pace.

After that time, its temperatures dropped sufficiently low to produce visible light. As the Cosmos continued to evolve, that light slowly underwent a process called redshift, which literally shifted it from the optical portions of the electromagnetic spectrum to the microwave section.

Thus, the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) was born, a layer of residual photons left after the Big Bang. Within it, the CMB holds the history of the entire Universe, and astrophysicists are dying to get their hands on these data.

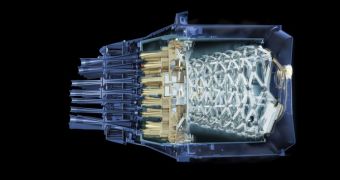

This is one of the main reasons why Planck was constructed in the first place. The extremely-sensitive observatory was launched back on May 14, 2009, from the Kourou Spaceport, in French Guiana, South America. It was carried to space aboard the same Ariane 5 ECA rocket that carried the ESA Herschel Space Observatory as well. The latter is the most complex spacecraft ever deployed.

Even though the HFI instrument was only supposed to complete two and a half surveys during the science phase of the mission, it managed to double its performances, concluding five full surveys. This gives researchers 200 percent more data than they expected, Space reports.

“Planck has been a wonderful mission; spacecraft and instruments have been performing outstandingly well, creating a treasure trove of scientific data for us to work with,” ESA Planck project scientist Jan Tauber explains.

The patterns inscribed in the very fabric of the CMB could be used to test theories such as those arguing that we are living in a multiverse, or those suggesting that the Universe is constantly expanding and then imploding, in a never-ending cycle.

There isn't really any other way for these ideas to be tested, except launch a mission such as Planck. If one thing's for certain, it's that experts will be busy with analyzing data from this mission for years to come.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //