Scientists in the United States are currently engaged in a series of researches that will allow them to determine which strains of the dangerous parasite Toxoplasma are the most dangerous for humans, as well as for other animals. These parasites are among the few that can infect any warm-blooded animal.

There are several pathogens that can infect a large number of species, but only a few that can multiply inside everything that has warm blood. Toxoplasma is one of the organisms in the latter category.

But, inside this species, there are many subgroups that are apparently more dangerous than the average. Discovering precisely which Toxoplasma parasites are the most dangerous is the goal of this study.

The work is being conducted by assistant professor of biology Jeroen Saeij, who is based at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in Cambridge. He explains that about 33 percent of the global population is already infected with Toxoplasma gondii.

Generally, the microorganism causes no health issues in people, but it can have adverse side-effects in the case of individuals whose immune systems have been affected by other diseases or infections.

Infections may also affect unborn fetuses inside their mothers' belies, who become infected with the parasite even before birth. The situation is worst in South America, where the most dangerous strains of the Toxoplasma live.

In Brazil, for example, infections with a particular strain of the parasite is the leading cause of blindness nationwide. The microorganism can readily infect cows, sheep, pigs and chickens, as well as plants grown for agriculture.

“It’s everywhere, and you just need one spore to become infected. Most cases don’t kill the host but establish a lifelong, chronic infection, mainly in the brain and muscle tissue,” says the MIT expert.

The end goal of this research is to figure out how the parasite is able to evade the immune system and establish a chronic infection. Saeij and the rest of the MIT team are already well known in the international scientific community for their work in this field.

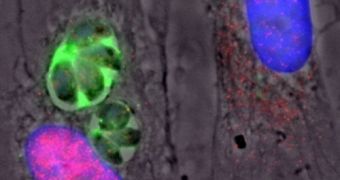

A few years ago, they managed to discover that rhoptry18 and rhoptry16 , two proteins secreted by Toxoplasma, were capable of hijacking the main processes taking place in the host cell.

In the new study, which appears in the January 3 online issue of the esteemed Journal of Experimental Medicine, the group explains the actions of the protein GRA15, which triggers inflammation in the host cell, and is responsible for determining how dangerous a certain microbe strain is for humans.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //