Over the past few years, methane levels around the world have began growing, and researchers are currently scrambling to make sense of why. They are also looking to determine the most potent sources for this dangerous greenhouse gas. One of the most likely candidates is permafrost.

While carbon dioxide (CO2) steals the spotlight when it comes to greenhouse gases (GHG), it has a lot less potential of heating the atmosphere than methane does. The latter is about 300 times more potent.

As such, keeping an eye on global concentrations of this chemical is a top priority for climate scientists. The spike in emissions is very worrying for a number of reasons, experts say.

First of all, there was no significant upward trend in methane release over the past several decades. From the 1970s to the 1990s, levels have held relatively steady, but they began growing again in 2007.

Giving the carbon compound's heat-trapping capability, scientists are looking at all potential sources, to determine which one increased its output. Studies have already shown that these sources include mining, fossil fuel processing, livestock feeding, landfills and permafrost.

The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has been keeping an eye on all of them for decades, and it releases the data it obtains in the NOAA Annual Greenhouse Gas Index.

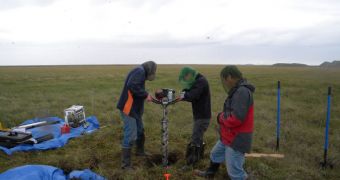

Wetlands in the tropics and permafrost in the Arctic are the most likely methane sources to have increased their output lately. Permafrost is basically frozen soil, and most of it is located in the Northern Hemisphere.

The carbon held up in these soils equals all known coal reserves, experts estimate. As temperatures increase around the world, permafrost melts, releasing more and more methane in the process.

Experts warn that this is a vicious circle – the more methane is released, the more temperatures rise, the more permafrost melts, and releases more methane. This feedback cycle has not yet kicked into full gear, but time is running out on us.

“NOAA’s Earth System Research Lab analyzes methane in air samples collected around the world,” explains the leader of the methane monitoring program at NOAA, chemist Ed Dlugokencky, PhD.

“The data we generate from these samples helps us understand global trends and details of the methane cycle. We do not see signs of a feedback cycle yet, but continued monitoring is very important,” he adds.

The latest predictions by NOAA show that permafrost surfaces are expected to shrink by 30 to 60 percent by 2200. This process would release vast amounts of CO2 and methane in the atmosphere.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //