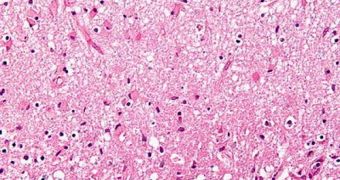

Brain probes are used for a variety of medical applications, but they have one major flaw, namely the fact that they scar brain tissue in the area where they are inserted in the brain. Now, experts develop a new type of probe, which turns pliable within minutes of being introduced inside gray matter.

This ability significantly reduces the amount of scarring that the brain receives during this process. The new device was created by investigators at the Case Western Reserve University (CWRU), and was tested on the cerebral cortices of lab rats.

According to the research team, the instrument is in fact a nanocomposite probe that drew inspiration from the most unlikely source, the dynamic skin of sea cucumbers. Apparently, these creatures' natural abilities are so remarkable that researchers sought to emulate them synthetically.

The benefits immediately became obvious, as the rats' immune response to the nanocomposite probes were significantly different from what researchers saw in mice that were prodded with standard, metal devices. At the same time, the former were able to make the brain heal faster.

In a paper published in the latest online issue of the esteemed medical Journal of Neural Engineering, CWRU experts explained how and why the brain responds the way it does when it detects a mismatch between metal and living tissue.

Understanding this can make it easier to improve the nanocomposite probes so that they elicit an even less-intense immune response. The next logical step will then be to translate this achievement to human patients as well.

In addition to metal wires, standard brain probes may also use silicon-based materials, but those too are significantly tougher than brain tissue. But the same effects are not made visible in the newest generation of such medical devices.

“The scar wall is more diffuse; the nanocomposite probe is not completely isolated in the same way a traditional stiff probe is,” explains the leader of the new experiment, CWRU professor of biomedical engineering Dustin Tyler.

“One hypothesis is that the soft material allows the brain to recover more quickly. Both probes cause the same insult to the tissue when inserted,” the expert says. He conducted the work with a number of colleagues at the university.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //