A couple of days ago, astronomers announced that the American space agency's planet-hunting telescope mission, Kepler, managed to identify its first rocky exoplanet. The finding now appears to hold, experts say. The star hosting the planet is one of the most well-analyzed in the world.

While we have no way of knowing how things are throughout the entire Universe, one thing is for sure – the Milky Way does not contain many rocky or small extrasolar planets.

Astronomers currently don't have any clear explanation about why that is, but the trend is unmistakable. Of the 500+ exoplanets we discovered thus far, only a handful are small enough to compare to Earth, and also rocky.

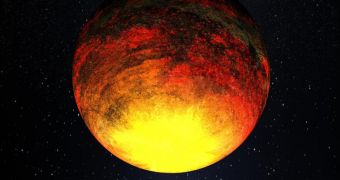

The planet that Kepler discovered is estimated to be about 1.4 times larger than our own, and has been calculated to have a density of 8.8 grams per cubic centimeter. This places it squarely in the rocky planet category, experts say.

According to astronomers, the star Kepler-10, which hosts this object, is one of the most well-characterized cosmic fireballs in the Universe. This is what allows them to be so sure that they finally found a rocky exoplanet.

Kepler-10b made its presence known through a signal experts picked up in 2009. In order to analyze it further, they decided to use Kepler to look at the object, which lies some 560 light-years away.

One of the most important aspects of the research was measuring the brightness oscillations the star exhibited in tremendous detail. This is one of the few available methods for detecting exoplanets.

What telescopes do is they keep an eye on distant stars, and wait for small variations in their apparent brightness. If this happens, then it's an indicator that something passed in between the observatory and its target.

Seeing how comets and asteroids are too small to cause any variations, the only possible explanation for the periodic dimming is the presence of an exoplanet, Space reports.

Kepler-10b caused a 0.015 percent brightness drop in its parent star. The fact was confirmed by the Hawaii-based Keck Telescope, which confirmed that the planet was tugging on its parent star via gravity, making it wobble slightly.

The announcement was made at the winter meeting of the American Astronomical Society (AAS 2011), by the leader of the research team, Natalie Batalha. She is based at the San Jose State University Department of Physics.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //