The fact that species react to their environment through a wide range of adaptations is well known today. Another confirmation of this came in a recent study, where scientists showed that prehistoric predators featuring large teeth also tended to have strong bones in their forelimbs.

This is an example of a suite of adaptations coming into play at the same time, so as to allow predators to become very efficient, and increase their chances of survival. Details of the new investigation appear in the January 4 issue of the scientific journal Paleobiology.

The clearest examples of toothy predators are extinct cats such as saber-toothed tigers. But other species sported the same adaptations as well, including the false saber-toothed cats called nimravids and the carnivore family known as barbourofelids.

According to paleontologist Julie Meachen, these families of species developed long before the earliest cats appeared, and all of them featured strong bones in their forelimbs, in addition to knife-like teeth. This suggests that this particular combination of traits evolved multiple times throughout history.

Meachen is based at the National Science Foundation (NSF) National Evolutionary Synthesis Center (NESCent) in Durham, North Carolina. She explains that one major drawback long, sharp teeth have over current conformations is that they are very fragile and susceptible to damage from sideway forces.

“Cats now have canines that are short and round in cross-section, so they can withstand forces in all directions,” Meachen explains. The reason for this may be that the advantages of having sturdier teeth eventually outweighed those of having sharper teeth.

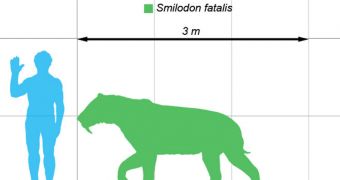

The expert says that a study she conducted on the saber-toothed cat Smilodon fatalis back in 2010 revealed an interesting possibility about how these creatures hunted. She proposes that the felines used their forelimbs to immobilize and kill prey, and used their teeth exclusively to inflict massive damage.

Interestingly, Meachen discovered a correlation between teeth and forelimbs. The thinner and more vulnerable teeth were (therefore, longer, sharper and more oval), the larger the forelimbs. This suggests a transfer of “responsibility” for killing prey from fangs to claws.

“This is a nice demonstration that selection usually operates on suites of traits to generate solutions to environmental challenges,” says NSF Biological Sciences Directorate program director Saran Twombly. The BSD funds NESCent.

“In this case, the key to being an efficient predator integrated canines and forelimbs across different groups of felids and led to the development of different combinations of these traits. It was the combination, rather than any single trait, that allowed a diverse group of organisms to thrive as predators,” the expert concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //