The elephants' fate is in our hands, because we're the ones who influence two main factors menacing their populations: habitat loss and the illegal ivory trade. At the beginning of the 20th century, there were 3-5 million elephants in Africa.

Then, the hunt was practiced mainly by the Arab ivory smugglers and by European/American hunters, some of them quite famous (like Hemingway). Back then, there were few hunters, and the elephants were many. But the dramatic decline started at the middle of the 20th century, during decolonization and the subsequent bloody civil wars.

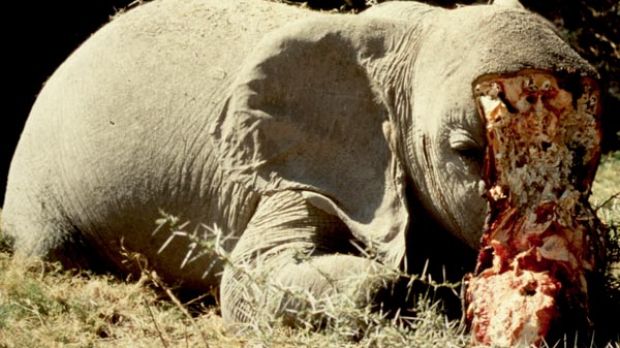

Today, there are about 500,000 elephants in Africa, and in the last 35 years, over 1 million have been hunted, 80 % by poachers. Hunger and poverty haunting over 60 % of the Africa's population push the people towards poaching. About 1,500 elephants could be killed weekly by poachers (about 70,000 annually), by riffles or poisoned arrows, gaining no more than 30 Euro ($ 45) for each ivory. The illegal ivory represents 90 % of its trade.

90% of the ivory is exported to Japan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, where the kilogram of ivory is sold with 80 Euro ($ 113). And one piece of ivory can have tens of kilograms... In Japan, the ivory industry employs thousands of workers, and from ivory they make jewels, ornamental objects, seals, billiard balls, and piano keys. Other importing countries are Spain, Portugal, Belgium and UAE.

But the real danger doesn't come from these people wandering through the forest and the savanna; it's the traders that make an international trafficking network. The annual illegal trade of 'white gold' moves about 705 million Euro (around $ 1 billion), of which only 7.5 million Euro ($ 10.5 million) reach the pocket of the Africans.

The ivory trade has been banned internationally by CITES in 1989, 1992 and 1994, but with scarce results. Some African nations opposed the ban in 1989: Zimbabwe, Burundi, Malawi, Botswana, Mozambique and South Africa, claiming they have effective methods of preserving the species, and they lose this way thousands of dollars destined to habitat conservation and compensations for the farmers (a sole elephant can destroy in one night a sole corn field, that ensure the subsistence for one year for a whole family).

In 1999, as a result of the pressure coming from these countries and many others, CITES authorized the exceptional sell of 60 tonnes of ivory to Japan, amount stored in Zimbabwe, Namibia, and Botswana. In 2000, these countries together with South Africa had a series of discussions during a Nairobi meeting with Kenya and India, the latter two being in favor of another charge of 54 tonnes to ...of course, Japan.

These authorizations, even if small, fuel the poaching phenomenon. Even in Kenya, the elephant poaching increased after the CITES authorizations. WWF firmly opposes these accords.

Besides anti-poaching, another danger for the elephants is the creation of large natural reserves with forested passage ways between them, facilitating the elephants' access to food and drink and avoiding the isolation of small populations. Captivity breeding would ensure for the elephants a genetic bank, delivering a healthy population for the next 200 years.

But besides the general poverty that helps poaching, there is also the corruption of the African authorities, that allows the kills and legalize the result of the poaching. For example, in Burundi, many hunters bring to this countries ivories from animals hunted in Tanzania, Kenya or Zaire, and from there, they export them with legal papers to Europe and Far East.

Even African governments fail to intervene in the ivory traffic, much less get involved in it, because it all comes down to money. Amongst the 37 nations having elephants in their fauna, there are some of the poorest in the world. The ivory also 'fuels' many armies and guerrillas. In Equatorial Guinea, soldiers kill elephants that cross the border from Cameroon. During the Angolan civil war, the rebels obtained their main income from the ivory got from 100,000 elephants killed in 10 years. In Kenya, poachers plummeted in 15 years, since 1973, the elephants' population from 130,000 to 17,000. Since then, the riffle was changed by the photo camera, and the huge natural reserves have turned tourism in the main income for Kenya. Remember the scene with the Kenyan president burning tonnes of poached ivory?

In many countries, rangers are authorized to shoot the poachers. But this does not stop them, as poaching levels are increasing in Kenya.

Also, this happens in Zimbabwe, where hunting as a sport is allowed. This 'sport' provides - from selling the elephant ivory, skin and meat - $30,000 per animal. The Zimbabwe government (and not only) says that the sport hunt helps the elephant's conservation, especially the money required for its habitat preservation.

But no African country invests the monthly $200 for square km necessary to secure the elephants and rhinoceros (also persecuted), as most of them lack the resources required for taking care of their environment.

Some say that the best method is to burn all the ivory coming from already dead animals and to be firm in the ban and traffic control.

In Southeast Asia, the main menace is the human population boom, the farming, and the deforestation. Unlike the African 'cousin', the Asian elephant is easy to domesticate and has been used by people for centuries. The deforestation comes with a double cut for the Asian elephant: it deprives elephants of food and exposes them to the sun, by which this species, unlike the African one, is affected.

About 4,500 survive in Sri Lanka. India holds the largest population: 20 to 30,000. In Bangladesh, the tek trees, tea and rubber trees have pushed the elephants to the steepest and remotest forests.

Modern elephants split their evolutionary lines about 5 million years ago. Their ancestors emerged 50 million ago, resulting over 300 fossil species of the elephant's relatives. Now, there are three types of elephants: two Africans and one Asian. There is the African forest elephant (Loxodonta Africana cyclotis) and the African savanna elephant (L. a. Africana). The first is smaller, with smaller tusks, living in the equatorial forest, the other in savanna, deserts, and drier woodlands. This is the largest land mammal: 3 m (10 ft) tall and with an average weight of 7.5 tonnes for the bulls. The tusks can be 3 m (10 ft) long, and while the female's are smaller, they are worn by both sexes. The record for males is a tusk of 3.5 m (12 ft) in length and 107 kg (260 pounds) in weight, while for the females - 18 kg (40 pounds).

The Asian elephant (Elephas maximus) is smaller; besides, very few females develop tiny tusks, and in the case of this species not even all the males are tusked. In some populations there is no tusked individual, because centuries of poaching eliminated all the tusked individuals.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //