According to a new series of scientific observations, the Earth's mantle is moving faster in some spots than researchers first calculated. The mantle is the layer of molten rock that covers the planet's solid core, and lies just beneath the tectonic plates on which Earth's oceans and continents lie. Researchers have just discovered that the movements of this planetary layer can easily be accelerated around subduction zones, which are the areas where tectonic plates move one above the other, and then sink into the mantle, LiveScience reports.

The places where tectonic plates meet can be classified into two categories. In the first, the plates rub against each other, but the general trend is for them to grow further apart. This is the case in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, where plates are actually growing in size. Lava exists from various underwater volcanoes, and deposits new layers of rock, pushing Europe and Africa further away from America with each passing day. The movements are too slow to notice, and the tectonic plates themselves move painfully slow.

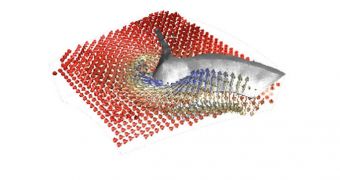

The second category is represented by subduction zones, where tectonic plates collide against each other head-on, or at an angle. The heavier plate moves under the lighter plate, and then into the mantle, causing earthquakes, tsunamis and volcanic activity in the process. As the heavy ones start to enter the mantle, and melt due to the extreme pressure and heat, they also make the magma in the area move faster under the surface plates. This is the conclusion of a new study conducted by US researchers at the University of California in Davis (UCD), led by associate professor of geology Magali Billen.

“Our model suggests that some parts of the mantle are moving at screaming speeds compared to what we can observe directly at the Earth's surface. There is much more mixing and more rapid transport of heat in these regions of the Earth than we suspected,” the expert explains. Additional details of the groundbreaking investigation appear in the May 20 issue of the esteemed scientific journal Nature.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //