An exoplanet identified by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in August was recently proven to have a mass roughly equal to that of Earth. Previous studies have determined that the celestial body also shares our planet's size.

For this research, astronomers used data from two telescopes, and studied the amount of wobble displayed by the exoplanet's parent star, Kepler 78.

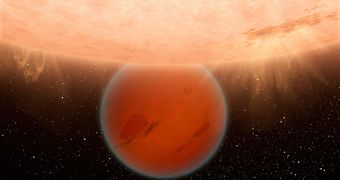

Located approximately 400 light-years away, the planet Kepler 78b is about 1.2 times the size of Earth, but 1.7 times more massive. Accordingly, the density of the planet was calculated at about 5.3 grams per cubic centimeter, echoing our planet's own density, of 5.5 grams per cubic centimeter. These values are important because they turn Kepler 78b into the smallest well-defined exoplanet.

Kepler 78b revolves around its parent star in just 8.5 hours, whereas Earth takes 365 days to do the same. The exoplanet is extremely close to its sun, meaning that its surface is roughly 2,000 degrees hotter than that of our planet.

The new world's mass was inferred by using data from the Keck Telescope in Hawaii, which was able to take precise measurements of the Doppler shift exhibited by the distant star. Each planet exerts a small gravitational tug on its parent star, and the Keck Telescope is very well suited to measuring this type of interactions.

The study was led by MIT associate professor of physics Josh Winn and University of Hawaii professor Andrew Howard, who was also the lead author of the research. A paper detailing the findings was published in this week's issue of the renowned scientific journal Nature.

Kepler 78b is “Earth-like in the sense that it’s about the same size and mass, but of course it’s extremely unlike the Earth in that it’s at least 2,000 degrees hotter. It’s a step along the way of studying truly Earth-like planets,” Winn said in a statement. Additional data for the study were collected using NASA's Kepler Space Telescope.

While attempting to find a method to correct solar spot interferences that were hampering the research, the team was able to develop a way of measuring the rotation period of the distant star, calculated at 12.5 days. This period is much longer than the 8.5 hours it takes Kepler 78b to move around its parent star once.

The research was also supported by investigators from the University of California at Berkeley (UCB), the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA), the University of California at Santa Cruz (UCSB), and Yale University.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //