When our planet's hum was identified for the first time, many experts were puzzled by it. Some people even went as far as to panic and call it a sign of God. Over the years, as with all the superstitions, these ideas faded away, as science progressed. Now, we have come so far in studying this ultra-low frequency noise, that experts say it could potentially be used to map other planets as well. Mars is, obviously, the first choice, as it is within reach, and knowing its structure is important for future manned missions on its surface, Wired reports.

What has been plastically termed the “background buzz of the globe” is generated by ocean-wave interactions, especially along the western seaboard of the United States, in the eastern Pacific. The vibration is far too low to be picked up by human ears, which make out sounds in the 20 hertz-20,000 hertz range. The hum can be identified at a measly ten millihertz, several times below our minimum limit. It's doubtful that there are living things on Earth that can make it out, scientists say.

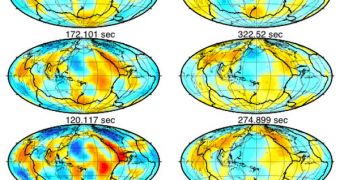

One of the phenomenon's most important and useful characteristics is that it slows down and speeds up as it moves through the planet's crust, depending on the sort of materials it comes across. When planetary scientists found that out, they used the same knowledge that applied to earthquake shock waves traveling underground – higher speeds were associated with colder, denser materials, whereas all waves moved slower through hot and less dense matter. In a paper that appears in the Thursday issue of the renowned journal Science, a team of experts at the University of Tokyo, led by scientist Kiwamu Nishida, published the first map of the Earth's interior, based solely on the hum's patterns.

“I think it looks good. It clearly has potential to be developed,” University of California in San Diego (UCSD) geoscientist Peter Gerstoft, who is also actively involved in studying our planet's background noise, says. The new imaging method “could conceivably be used in planetary exploration for investigating the deep internal structures of Mars or other bodies,” the Japanese authors write in their paper.

“As the existence of marsquakes is questionable, the applicability of conventional earthquake tomography is not guaranteed. However, Martian atmospheric disturbances might excite background long-period Rayleigh waves on this planet,” they add, saying that these waves would, in essence, represent the Red Planet's hum.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //