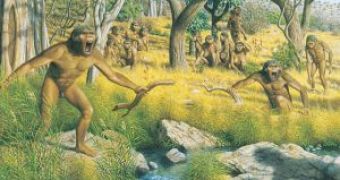

Australopithecus was the first lineage that split from a common ape ancestor of the humans and chimps 4 million years ago.

A new research points to the fact that these ape-like human ancestors kept short ape-like legs for 2 million years because a squat physique could have been a strong support in male combat over access to females. "The old argument was that they retained short legs to help them climb trees that still were an important part of their habitat. My argument is that they retained short legs because short legs helped them fight", says David Carrier, a professor of biology at University of Utah.

The research compared leg lengths and indicators of aggression in nine primate species, including human aborigines (a relatively natural population), but also apes (gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos, orangutans, black gibbons, siamang gibbons) and monkeys (olive baboons and dwarf guenon monkeys).

Australopithecus, which gave birth to the current human genus Homo, were about 3 feet 9 inches (115 cm) tall in the case of females and 4 feet 6 inches (135 cm) tall in the case of males and lived from 4 million to 2 million years ago. "They had relatively short legs - longer than chimps' legs but shorter than the legs of humans that came later," said Carrier. "Among experts on primates, the climbing hypothesis is the explanation. If you are walking on a branch high above the ground, stability is important because if you fall and you're big, you are going to die. Short legs would lower your center of mass and make you more stable", he added.

But his research points to combat theory because "with short legs, your center of mass is closer to the ground. It's going to make you more stable so that you can't be knocked off your feet as easily. And with short legs, you have greater leverage as you grapple with your opponent."

Carrier's hypothesis does not reject the climbing theory, but "evidence is poor because the apes that have the shortest legs for their body size spend the least time in trees - male gorillas and orangutans."

Short legs are rather not beneficial "to bridge gaps between possible sites of support when climbing and traveling through the canopy."

"The two hypotheses for the evolution of relatively short legs in larger primates are not mutually exclusive. Selection for climbing performance may result in the evolution of a body configuration that improves fighting performance and vice versa. All modern great apes - humans, chimps, orangutans, gorillas and bonobos - engage in at least some aggression as males compete for females," said Carrier.

Carrier investigated for each primate species typical hindlimb lengths and two physical traits linked to male-male competition and aggressiveness in primates: size ratio between male and female (the higher the aggressiveness between males in their competition for female, the higher the size difference between sexes) and the male-female difference in the length of canine teeth (fangs involved in biting during fights).

The results showed that hindlimb length correlated inversely to aggressiveness: species with higher male-female differences in body weight and canine length possessed shorter legs.

Arm length was not linked to aggression because they are employed "for other things as well: climbing, handling food, grooming. Thus, arm length is not related to aggression in any simple way."

Even after correcting the size factor (larger primates, except humans, tend to have short limbs) and kinship factor (if three closely related species have short legs, it might be due to the relationship - an ancestor with short legs - and not aggression), the short legs were still significantly linked to aggressiveness.

Except for humans, females in each primate species possess relatively longer legs than males. "If it is mainly the males that need to be adapted for fighting, then you'd expect them to have shorter legs for their body size," said Carrier. There is one exception: the bonobos possess shorter legs than chimps, even if they are less aggressive. "The correlation between short legs and aggression may be imperfect because legs are used for many other purposes than fighting. Humans "are a special case" and are not less aggressive because they have longer legs," said Carrier.

Australopithecus were stopped in their evolution by this physical tradeoff between aggression and economical walking and running.

They could stand their ground when shoved, but their could not run on long distances with their short legs, unlike the long-legged humans, who are also good fighters.

In a previous research, Carrier showed that Australopithecus evolved into long-legged early humans only when they learned to fight with weapons. Yet, "we don't really know how aggressive australopiths were. Given the aggressive behavior of modern humans and apes, we should not be surprised to find fossil evidence of aggressive behavior in the ancestors of modern humans," said Carrier.

"This is important because we have a real problem with violence in modern society. Part of the problem is that we don't recognize we are relatively violent animals. If we want to prevent future violence we have to understand why we are violent. To some extent, our evolutionary past may help us to understand the circumstances in which humans behave violently. Nevertheless, male-male competition doesn't fully explain human violence," added Carrier, pointing to other factors like hunting, competing with other species, defending territory and resources, and feeding and protecting offspring.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //