A theoretical physicist is stating that a second dimension of time could help physicists better explain the laws of nature. Now, the dimension of time has an important role in describing matter, gravity and other forces of nature, but something doesn't fit.

Einstein's theory of general relativity and the equations of quantum theory are very accurate at describing all the nuances of matter and other forces, from magnets to strong and weak nuclear forces, but his theory of gravity doesn't fit with quantum theory.

Physicists around the world are still trying to come up with a universal theory that could unify every other already existing law and equation, but have so far come up empty. It seems some piece is missing in the picture puzzle of physical reality.

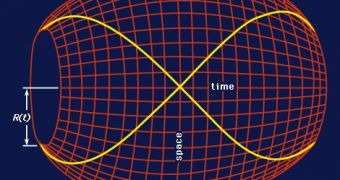

USC College physicist Itzhak Bars has been pondering the role of time in basic physics for a long time and thinks one of the missing pieces is a hidden dimension of time. As strange as it may seem, Bars believes that our Universe can have two times, which could make many of the mysteries of today's laws of physics disappear.

He thinks that other dimensions could exist, curled up in little balls, so tiny to notice that if you moved through one of those dimensions, you'd get back to where you started so fast you'd never realize that you had moved.

It's a concept extremely difficult to grasp with our limited perception, almost like asking a two-dimensional character drawn on a flat piece of paper to describe his width, when his world has none.

"An extra dimension of space could really be there, it's just so small that we don't see it," said Bars. He claims that a subatomic particle might detect the presence of extra dimensions, and that certain properties of matter's basic particles, such as electric charge, may have something to do with how those particles interact with tiny invisible dimensions of space.

Bars believes that the Big Bang that started the baby universe growing 14 billion years ago blew up only three of space's dimensions, leaving the rest tiny.

For now, his opinions are controversial, but if he's right and could prove it, it will change the way we think of some of the most basic processes in physics, like velocity, mass and the resulting momentum of a particle (mass times velocity).

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //