A collaboration of scientists from the University of British Columbia (UBC) and an industry partner were recently able to reverse diabetes in mice using stem cells. This is the first time this type of treatment was demonstrated successfully.

If these results are confirmed and duplicated, then there is a very real possibility that a cure for diabetes will be developed over the next few years. However, patients will have to wait for a while longer before they finally have access to a potential cure.

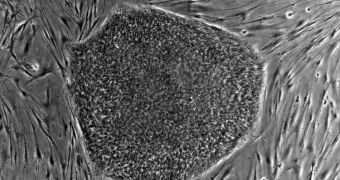

The new investigation was carried out on lab mice that had diabetes. Researchers led by UBC Department of Cellular and Physiological Sciences professor Timothy Kieffer were able to use stem cells to restore insulin production within the bodies of these animals.

The team conducted the research in collaboration with scientists from BetaLogics, a division of Janssen Research & Development, LLC, in New Jersey. They say that treating diabetes is a matter of restoring functionality to insulin-producing cells in the body.

What the team did was recreate the feedback loops that enable blood glucose levels to regulate the amount of insulin present in the bloodstream. These loops are disrupted in diabetics, which is why they need to take shots containing the hormone.

Details of the new investigation were published in the June 27 issue of the esteemed journal Diabetes.

According to the research team, it took between three and four months for the mice to recover from diabetes completely. In addition, the rodents' bodies were able to maintain the correct blood sugar levels even after researchers purposefully fed them sugar-rich diets.

Several months later, scientists removed cell samples from the locations where they first implanted them, and found that the cells displayed all the behaviors and characteristics of normal pancreatic cells.

“We are very excited by these findings, but additional research is needed before this approach can be tested clinically in humans,” explains Kieffer, also a member of the UBC Life Sciences Institute.

“The studies were performed in diabetic mice that lacked a properly functioning immune system that would otherwise have rejected the cells,” he goes on to say.

“We now need to identify a suitable way of protecting the cells from immune attack so that the transplant can ultimately be performed in the absence of any immunosuppression,” the investigator concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //