The results of a new scientific investigation from researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) indicate that the discovery of sulfurous molecules on a distant, extrasolar planet could be construed as an indication that life may have developed at that location.

Astrobiologists know that life here on Earth is based on carbon because of the vast number of chemical reactions that can take place with this element. At the same time, lifeforms evolved based on carbon because this is what we find in abundance on our planet.

But it's not at all impossible for life on other planets to be based on an entirely-different chemical, such as for example sulfur, phosphorus, or even arsenic. Microorganisms detected here show that life is tremendously resilient, even when it has to rely on chemistry belonging to another chemical than what they evolved to handle.

Also here on Earth, experts found bacteria that can feast on the sulfurous compounds that are released as mountains erupt in powerful explosions. It is conceivable that, if life occurred elsewhere in the Universe as well, it would have the same type of adaptability.

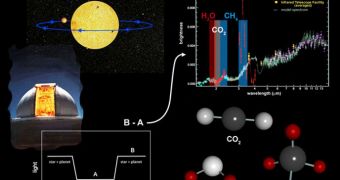

When surveying exoplanets' atmosphere, astronomers should always keep an eye out for the chemical composition of the air, MIT planetary science PhD student Renyu Hu explains. Such eruptions would imply the presence of sulfur in that space object's atmosphere.

At the same time, it would also indicate an active core, which is another important factor in the development of life. A spinning core produces a magnetosphere to shield the surface from radiation, and also provides heat that lifeforms could then enjoy.

“Hydrogen sulfide emissions from the surface would have a large impact on the atmospheric composition of a planet. Characterization of the atmospheres of exoplanets has been confined to close-in planets so far,” Hu explains.

Until now, astronomers have only been able to conduct exoplanetary atmospheric research only in a few instances, on planes that are located relatively nearby. But the Milky Way may have as much as 2 billion planets, of which at least several millions may be rocky, and about the size of Earth.

Hu and MIT colleagues Sara Seager and William Baines say that hydrogen sulfide is not by far the only chemical that can be used to remotely detect life on other planets.”We want to study as many as possible – look at many, many gases in Earth's atmosphere and see if they can be biosignatures as well,” Hu says

Details of his investigation were presented at a recent meeting of the American Astronomical Society, which was held on May 26, in Boston, Massachusetts, Space reports.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //