Researchers from Stanford University have found a clever – to say the least – way in which users can utilize a password without actually being able to recite it. To achieve the goal, they designed a game that relies on a combination between cryptography and neuroscience.

There are a lot of ways in which cybercriminals can get an internaut’s password. They can use malware, phishing campaigns, or they can simply force the victim to tell them the password in what’s known as a “rubber hose” attack.

If the first two attacks can be defeated with some common sense and a reliable piece of antivirus software, the rubber hose attack requires a bit more than that.

In a paper called “Neuroscience Meets Cryptography: Designing Crypto Primitives Secure Against Rubber Hose Attacks,” researchers Hristo Bojinov, Dan Boneh (Stanford), Daniel Sanchez, Paul Reber (Northwestern University), and Patrick Lincoln (SRI) explain how to defend against such attacks by using the concept of implicit learning. The experts have developed a clever computer game that plants a secret password in the participant’s brain, without him/her actually knowing it.

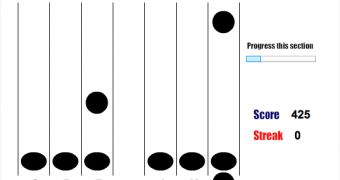

The game is simple. The player must intercept falling objects by pressing their corresponding keys. Without the user’s knowledge, during the 30-45 minute game time, a sequence of 30 positions is repeated over 100 times.

By repeating the sequence over and over, the user doesn’t actually know what he’s typing, but he is able to reproduce it.

“All of the sequences presented to the user are designed to prevent conspicuous, easy to remember patterns from emerging,” the scientists explain.

“The result is that while the trained sequence is performed better than an untrained sequence, the participant usually does not consciously recognize the trained sequence.”

The research is based on previous studies that have shown that sequences learned in this manner cannot be recited.

While in theory this method sounds good, in practice things are slightly different. For one, the password can still be obtained by an attacker by using eavesdropping (keyloggers or even the more physical “over the shoulder” approach).

Furthermore, the security mechanism is still not user-friendly enough, and it can be broken if the authentication system is compromised.

However, according to New Scientist, Bojinov believes that once the system is improved, it could be utilized for authentication systems that require the individual to be physically present when accessing a facility, for instance.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //