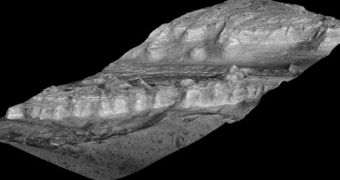

One of the most accurate sources of information that geologists have on a planet's past is its geological record, defined as the layers of rock that can be found underground at various depths. As the Earth, for example, undergoes changes and experiences volcanism, cometary impacts and tectonic movements, traces of all these are maintained in rocks, and become inestimable treasure troves for experts. The same holds true on any planet, and astronomers have now discovered a location on the Red Planet where the geological record, composed of many rock layers, is clearly visible.

Scientists managing the NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter (MRO) used instruments aboard the spacecraft to make this discovery. The mound of rock layers is about as high as the Rocky Mountains, and it lies within a crater spanning the surface of Connecticut. Because of its sheer size, the record still contains data on how things were set up at that location several billions of years ago, when the planet was still young. Possibly, it was also very different from how we know it to be now – a desolate, sandy desert, where nothing can survive.

“Looking at the layers from the bottom to the top, from the oldest to the youngest, you see a sequence of changing rocks that resulted from changes in environmental conditions through time. This thick sequence of rocks appears to be showing different steps in the drying-out of Mars,” scientist Ralph Milliken says. He holds an appointment at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), in Pasadena, California.

In a paper appearing in the latest issue of the respected scientific journal Geophysical Research Letters, the researcher and his coauthors report that they have discovered clay minerals very low in the layers. These minerals only form in wet conditions, and the discovery is in tune with proposals that the Red Planet lost its water at least one billion years ago, Space reports.

“If you could stand there, you would see this beautiful formation of Martian sediments laid down in the past, a stratigraphic section that's more than twice the height of the Grand Canyon, though not as steep,” Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory expert Bradley Thomson explains. He is one of the two coauthors for the new paper, alongside California Institute of Technology (Caltech) researcher John Grotzinger. Caltech manages the JPL for NASA.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //