New discoveries hint at the fact that comets have far less carbon on their surfaces and at their cores than initially suspected. Experts say that this knowledge may force a rethinking of the role they attribute to these space bodies in the emergence and subsequent development and evolution of life on Earth.

For years, biologists and planetary scientists have argued that comets played a critical role in promoting the appearance of life here. The objects may have done through a variety of means.

They may have disturbed the crust, forcing more volcanic eruptions, or they may have heated up the locations where they made impact, or they may have brought zombie microorganisms from space.

The truth is that their exact influence on our world will most likely remain mysterious until the end of time. But what researchers can say is whether the comets played a role – regardless of its nature – in a certain process or not.

What the new discoveries imply is that the celestial bodies may have not been involved so deeply in a number of process they were until now believed to have triggered.

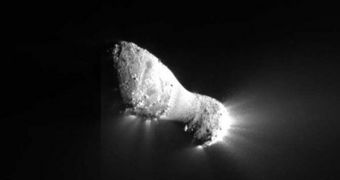

Past investigations have revealed the existence of carbon-loaded molecules on these objects, alongside biomolecules such as amino acids. Using the Galaxy Evolution Explorer (GALEX) satellite, experts recently analyzed one particular comet in detail.

The object, called C/2004 Q2 (Machholz), had a gas and dust envelope that reflected ultraviolet light, and the orbital instrument was used to study the nature of the radiation the structure emitted.

Ultimately, the goal of the work was to determine how long it takes for carbon atoms to become ionized. GALEX revealed that this process unfolds very quickly, in just 7 to 16 days, Space reports.

This means that the total amount of carbon on comets may have been exaggerated by at least a factor of two, according to Planetary Science Institute space physicist Jeff Morgenthaler. He explains that carbon becomes ionized when hit by enough solar radiation.

The new study implies that solar winds actually play a more important role in changing these atoms than thought. “This had been predicted earlier, but until now no one had quantitatively put all the pieces together and done a measurement that confirmed it,” the expert says.

He and his team detailed their findings in a new scientific paper, which was accepted for publication in the January 1 issue of the esteemed Astrophysical Journal.

The conclusions “could rein in speculation as to what carbon-containing molecules comets might have been contributing to Earth,” Morgenthaler concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //