A new scientific study seems to suggest that children are far better at detecting the tricks behind optical illusions than the elderly. This ability may be partially owed to the different way in which the two age groups size up the target objects, and relate their sizes to everything around them. This may also mean, scientists say, that the brain's ability to make out the context of visual scenes develops over time. As soon as it is set-up, the cortex becomes unable to focus on parts of scenes, and thus looses its ability to make out the deceiving parts of optical illusions, Wired reports.

The new study was conducted by a team of scientists at the University of Stirling, in Scotland, which was led by expert psychologist Martin Doherty. Details of the new work appear online, in the November 12 issue of the respected scientific journal Developmental Science. In the research, the group concludes that even 10-year-olds do not have adults' ability to attune their brains to the visual context. This means, the study leader adds, that this context can be easily manipulated if it's targeted at adults, eliciting whatever reaction the manipulator wants.

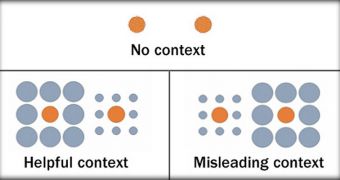

When subjected to a task more commonly known as the Ebbinghaus illusion, the brains of 7-year-olds showed no signs of altered size perception, the experts add. “When visual context is misleading, adults literally see the world less accurately than they did as children,” Doherty adds of the results. A similar investigation was conducted by the same team in Japan and the results were in tune with the one obtained in Scotland. This can only mean that the trait spans all human brains and is therefore an evolutionary trait. In Japanese adults, a higher tendency of watching the visual context was found to exist, when compared to adults in Scotland.

According to psychologist Carl Granrud, based at the University of Northern Colorado, in the US, the new study is very convincing in the evidence it presents, but also very surprising in its results. When exposed to other types of tests, such as those that exhibit two seemingly-different horizontal lines (which are actually the same length), flanked by diagonal lines, the children also take into account the visual context. Why they do not do so in the case of Ebbinghaus illusion is anyone's guess, but the matter may be worth more investigating, he adds.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //