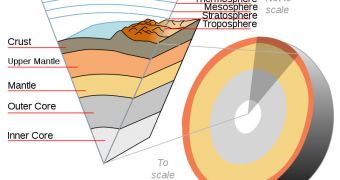

For many years, science books have been presenting the areas underneath the surface of the Earth, the upper and lower mantles, and the core, as regions that are relatively homogeneous. However, experts know that this is as far from the truth as it gets. These planetary layers are actually riddled with all sorts of structures that never really mixed into the magma, as well as with areas with varying densities and temperature. The same holds true for the core, the central region of Earth. Planetary scientists say that it is mostly composed of iron alloys, but they now add that these elements have crystallized in a very interesting manner.

Experts at the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, led by geologist Maurizio Mattesini, reveal that the core allows for seismic waves coming along on the north-south axis to move very fast. On the other hand, waves moving on the east-to-west line have a much tougher time getting through, and the reason for this is that the iron alloys appear to have crystallized in an unexpected fashion. In a study published in the latest issue of the esteemed journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), the group says that the anomaly is visible even at an atomic level.

“The structure of the atoms looks different in one direction than the other,” adds Stanford University geologist Norm Sleep, who did not participate in the recent investigation. “The center of the Earth is literally a crystal,” says California Institute of Technology (Caltech) geologist David Stephenson. He reveals that, over the billions of years our planet has been around, the core has evolved gradually as well. As such, it is now believed to be a collection of crystal aggregates, rather than a single, large one. The central region of the planet is thought to be a solid iron ball about 750 miles in diameter, Wired reports.

What the new data would seem to suggest is the fact that the crystal accumulations basically received a particular alignment as they were becoming solid, rather than forming at random. If the latter were the case, then the planet's interior would have allowed for seismic waves to pass readily in any direction. The new idea is also supported by the fact that lab-based simulations of particular kinds of iron crystals showed an intimate correlation with data sets collected by geologists and seismologists, on the speed of seismic waves.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //