According to the conclusions of a new scientific study, it would appear that following certain types of diets can have a positive effect on the human body, protecting it from the development of cancer, and stopping the spread of tumors that are already formed.

This effect was observed for people who consumed diets that were very rich in proteins, but extremely low on carbohydrates. These individuals were at a reduced risk of developing cancer, the team says.

At the same time, these diets appeared to have a beneficial effect on patients who had already developed cancer. Tumor growth in these individuals was found to be significantly reduced, even stopped.

Details of the new research appear in the latest issue of the American Association for Cancer Research (AACR) journal Cancer Research, a leading medical publication dealing with making studies about the causes, effects and potential cures for cancer widely available.

The research team that led the new investigation says that the work was carried out on lab mice, but adds that the animals provide a good analog for the human body. The study promises to open up new avenues of research in oncology.

“This shows that something as simple as a change in diet can have an impact on cancer risk,” explains British Columbia Cancer Research Center distinguished scientist and lead study researcher Gerald Krystal, PhD.

“Many cancer patients are interested in making changes in areas that they can control, and this study definitely lends credence to the idea that a change in diet can be beneficial,” says Cancer Research editor-in-chief George Prendergast, PhD, who was not a part of the new research.

In the new experiments, mice were divided into two groups, each of which assigned to a different diet. The first group was made to eat a typical Western diet, while the latter a modified South Beach one.

The Western diet was made up of 55 percent carbohydrates, 23 percent proteins and 23 percent fat, while its counterpart was 15 percent carbohydrates, 58 percent proteins and 26 percent fat.

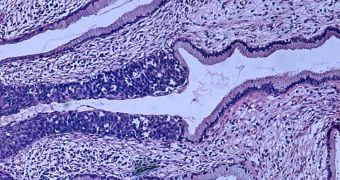

Mice in the second group exhibited slower tumor growth than their peers in the first one. Within the first year of life, more than 50 percent of the mice in the Western diet group developed cancer, and 70 percent of them died before reaching mice's average lifespan of two years.

In the second group, only 30 percent of the mice got cancer, and only half of those died, the research team concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //