According to the most recent study on the nature of tumors, it would appear that some cancerous cells are able to stop, or at least delay, the spread of the disease through the body. The discovery could give rise to new therapies that use this capability for curing cancer.

Common cancer treatments in use today are designed solely to destroy all cancer cells they come across, with no exceptions. What the study suggests is that, in doing so, oncologists may also be inadvertently destroying a control mechanism that they could instead be using.

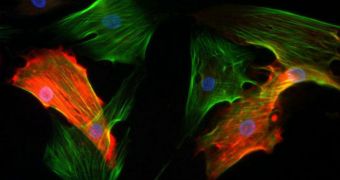

Researchers at the Northwestern University say that doctors may even be making tumors more aggressive, especially when targeting them with a therapy called angiogenesis inhibition. This approach targets cells called pericytes.

This cellular subgroup is responsible for preventing the spread of cancer through the body, a process called metastasis. When this occurs, there are no more chances for that patient to survive. By that point, the cancer has already spread to all major organs.

In the study, which was released yesterday, January 17, researchers highlight the importance of conducting additional studies on tumor-cell composition. If we understand what we're dealing with in more detail, then it may become possible to develop more effective therapies against this condition.

The work was carried out at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, in Boston.

“Not everything present in the tumor is bad for us. Pericyte functionality and coverage on blood vessels, is important because it allows the blood vessels to be leak-free and normal,” Harvard Medical School professor of medicine Dr. Raghu Kalluri says. He was also the senior author of the study.

The reason why pericytes are targeted in standard cancer therapies is because destroying them limits blood flow to the tumor, delaying its growth. But this may come at a hefty price, the study suggests, since the approach also makes cancerous cells more likely to become increasingly aggressive.

“Many tumor therapeutics were actually developed based on their ability to minimize cancer growth. Angiogenesis inhibition has been sort of a predominant cancer therapy, but the problem is angiogenic inhibitors do nothing to prevent recurrence on their own,” Dr. Carole LaBonne explains.

The expert is a program leader for the Tumor Invasion, Metastasis and Angiogenesis Program, which is based at the Northwestern University (NU) Robert H. Lurie Comprehensive Cancer Center.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //