A gigantic telescope is about to be built in Antarctica and scientists hope to be able to catch a glimpse of neutrinos, the exotic particles traveling almost at the speed of light for millions of miles through space, passing right through planets.

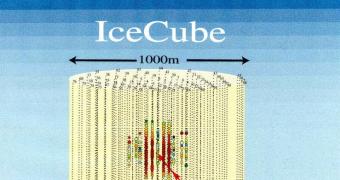

The name of the telescope is "IceCube" because it consists of thousands of spherical optical sensors (photomultiplier tubes, or PMTs) deployed in the ice cap of the South Pole, at depths between 1,450 and 2,450 meters, forming a cubic kilometer of ice transformed into a high power space instrument.

The main institution involved in the project is the University of Wisconsin and the University of Delaware is building the telescope's surface array of detectors, aptly named "IceTop."

Neutrinos are elementary particles traveling close to the speed of light, lacking electric charge and able to pass through ordinary matter almost undisturbed, they are extremely difficult to detect. Most neutrinos which pass through the Earth emanate from the sun, and more than 50 trillion solar electron neutrinos pass through the human body every second.

Thomas Gaisser, Martin A. Pomerantz Chair of Physics and Astronomy, is leading the UD project, that aims to take a closer look at the heavens and some of the most distant and violent events in the cosmos.

"IceCube is already the world's largest neutrino telescope although it is less than half-finished," Gaisser said. "Its purpose is to use neutrinos as a novel probe of high-energy astrophysical processes to reveal their inner workings, which are obscured for ordinary telescopes using light and other wavelengths of the electromagnetic spectrum."

The finished instrument will have more than 70 strings, each containing 60 optical detectors, frozen over a mile-and-a-half deep in the Antarctic ice cap. The sensors are deployed on "strings" of sixty modules each, into holes melted in the ice using a hot water drill.

"The purpose of IceTop on the surface is to detect high-energy cosmic rays that interact in the atmosphere above IceCube," Gaisser noted. "By detecting the same events with IceTop and the deep detectors of IceCube, we expect to get new information about the origin of the most energetic particles in nature. At the same time, the surface detectors help IceCube reject the background of downward cosmic-ray events that obscures the signals of neutrinos coming up through the Earth from below."

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //