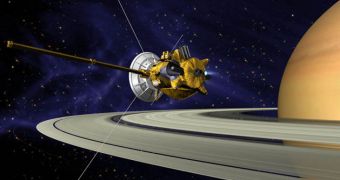

According to an announcement made by the American space agency, it would appear that the NASA Cassini probe, currently in orbit around Saturn, will regain full functionality in its scientific cameras no earlier than November 24.

The spacecraft is currently in safe mode, after a glitch on its onboard computer forced it to shut down non-essential systems, in order to prevent further damage. Experts managing the mission are convinced that the fault will have no serious, long-term effects.

The probe triggered the safe mode event, an automatic failsafe measure, at around 7 pm EDT (2300 GMT) on Tuesday, November 2. Since then, all science activity has stopped.

Scientists at the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), in Pasadena, California, who manage the mission for NASA, say that preliminary analysis shows the spacecraft to be in perfect health.

But JPL Cassini program manager Bob Mitchel said in a statement that the space probe, which has been orbiting the gas giant since July 1, 2004, will remain offline for science until November 24.

This delay will be used by programmers at JPL to try and make even more sense of what happened on Cassini, remove all damages, and develop methods of ensuring this doesn't happen again.

Engineers have already determined that the most likely cause for the recent malfunction was a faulty program code line, that somehow made its way to the orbiter.

Analysis determined that the information contained within was corrupted as the beam carrying the data headed from Earth to Saturn. What's more peculiar is that the probe's computers did not reject the lines of code, even if this is what usually happens in such circumstances.

A solar flare may have been responsible for corrupting the signals, scientists now believe. These events spew jets of charged particles from the surface of the Sun, and they are known for their ability to disrupt communications back on Earth.

The main regret that mission controllers have is that the spacecraft missed a flyby of Saturn's largest and most interesting moon, Titan.

On the bright side of things, until Cassini’s mission ends, in 2017, NASA has 53 more flybys of the moon planned, in addition to flights around other Saturnine satellites, Wired reports.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //