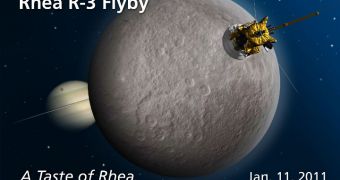

Officials from the NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL), who manage the space agency's Cassini mission to Saturn, announce that the spacecraft conducted a flyby of the Saturnine moon Rhea today, January 12.

The icy moon was analyzed with a very specific purpose in mind, and that was making more sense of how the gas giant's amazing ring system was formed, and how it is maintained to this day.

One of the most interesting thing about the rings is that, for all their incredibly-large surface, they are incredibly thin even at their thickest locations. This has led astronomers to wonder about the mechanisms that formed them, and that keep their shape and size constant.

Some have proposed that several of Saturn's moon may play a role in what has been termed “resupplying” the rings with fresh material. Enceladus, for example, spews out water-ice particles from cracks at its south pole, which then go on to feed one of the rings.

During this new flyby, which took place at 4:53 am UTC, or 10:53 pm Pacific Time on Monday, January 10, Cassini descended to as little as 69 kilometers (43 miles) above the surface of Rhea.

JPL experts hope that the space probe's instruments were able to collect new data, that could give them more insight into Saturn's extensive ring system. The reason why Rhea was selected for this investigation is that it has virtually no atmosphere.

This “allows Cassini's cosmic dust analyzer and radio and plasma wave instrument to detect the dusty debris that flies off the surface from tiny meteoroid bombardments,” JPL experts say.

“Counting these dust particles ejected from Rhea's surface helps scientists estimate the bombardment rate for the Saturn system and how often the icy rings have been polluted by particles from other places in the solar system,” they add.

“Understanding the contamination rate will enable scientists to improve estimates of the age of the rings,” the team goes on to say. Past studies aimed at doing the exact same thing failed because the data were contaminated by the E ring.

This is the ring that is fueled by Enceladus. Due to the new, constant addition of particles, it's very difficult to estimate the structure's age. But, by looking at th rings around Rhea, the contamination effect is removed from the picture.

The new mission was the third close flyby of Rhea that Cassini carried out. The orbiter has been surveying Saturn, its rings and its moons since achieving orbital insertion around the gas giant, on July 1, 2004.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //