A group of investigators based at the Rice University has recently been awarded one of 16 grants from the US Department of Energy (DOE). The money are to be used for developing advanced technologies, capable of removing and storing carbon dioxide gas released from power plants.

At this time, this is one of the most important sources of pollution worldwide, accounting for a vast proportion of greenhouse gases that feed global warming and climate change. Therefore, acting to reduce emissions could have immediate, positive consequences on the environment.

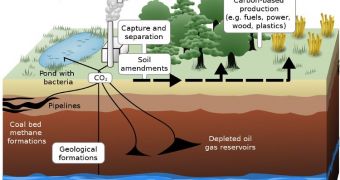

Carbon capture and storage (CCS) technologies usually consist of mechanisms placed on power plant smokestacks, where they filter out CO2 from other compounds being released into the atmosphere. The chemical is then moved to a storage area deep underground.

The Rice research group is just one of 16 the DOE selected for such a critical study. The team's work will mostly be focused on power plants powered by coal and natural gases, which are the most polluting of the bunch.

According to official statistics, a 500-megawatt coal-based power plant releases sufficient amounts of CO2 every single day to fill up the massive Houston Astrodome 400 times over.

“The sheer quantity of carbon dioxide emitted by power plants represents both a daunting challenge and a terrific opportunity,” explains Sumedh Warudkar, who is a graduate student and study co-investigator on the Rice team.

“It's a difficult technical challenge to capture such a large volume of CO2, but if we can find a feasible way, it could really change things,” the investigator goes on to say. Warudkar's adviser is George Hirasaki, who is also the principal investigator on the DOE grant.

One of the main issues the team needs to overcome is energy efficiency, meaning that they have to improve on existing CCS technologies. In order to have any effect, the latter must consume as much as 20 percent of the Steam that would otherwise be used to produce electricity.

The Rice investigators may need to rethink smokestack designs altogether, although that might make their new technology hard to apply at a large scale. Still, in time, a successful approach could make its way into the mainstream.

“Because we're experimenting with a new process, a lot of optimization will be required,” Warudkar explains. The investigation is supported by a grant from the DOE National Energy Technology Laboratory.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //