Some time ago, researchers at the University of California in Los Angeles (UCLA) announced the development of a brain-imaging technique that enabled them to assess the neurological changes produced by cognitive decline. Now, they report that the approach can also predict dementia risks.

In a paper published in the February issue of the journal Archives of Neurology, the team explains that their technique is able to both track and predict cognitive decline over a 24-month period. What they did was essentially take their previous work the logical step forward.

Researches such as this are extremely important, especially for countries in the developed world, where aging is the overall trend in the general population. As the baby boomer generation is getting older, the number of those who suffer from either mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia is rising.

MCI – a predictor for conditions such as dementia and Alzheimer's disease – currently affects around one in five people above the age of 65. Dementia has a lower incidence in the same age group, of only 10 percent, but both these figures are on the rise.

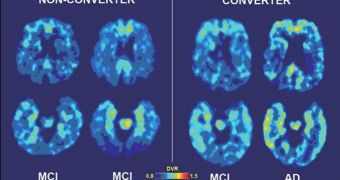

In order to determine which individuals are more likely to develop MCI or dementia, investigators at UCLA decided to use the chemical marker FDDNP in combination with positron emission tomography (PET) brain scans.

FDDNP is very versatile, and able to bind to both plaque and tangle deposits. Proteins such as tau and beta-amyloid create tangles and plaques, respectively, in the demented brain, hampering the functionality of neurons and eventually leading to degeneration.

“We are finding that this may be a useful neuro-imaging marker that can detect changes early, before symptoms appear, and it may be helpful in tracking changes in the brain over time,” the UCLA Parlow–Solomon professor on aging, Dr. Gary Small, explains.

The expert, who authored the new study, also holds an appointment as a professor of psychiatry at the UCLA Semel Institute for Neuroscience and Human Behavior. He highlights the fact that recent studies have demonstrated that dementia can be discovered in the brain decades before symptoms develop.

“We found that increases in FDDNP binding in key brain areas correlated with increases in clinical symptoms over time. Initial binding levels were also predictive of future cognitive decline,” concludes the UCLA Plott chair in gerentology, Dr. Jorge R. Barrio.

The US National Institutes of Health (NIH) and the US Department of Energy (DOE) provided the funding needed for this investigation.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //