It is a matter of status in Yemen to wear a dagger with rhino horn made handle, or to afford chewing tiger bone penis in China. These customs have put on the brink of extinction those species. Maya rulers made no exception: huge demand for symbolic species explains the decline in big mammals, like jaguars and tapirs, in ancient Central America, as pointed by a new research published in the Journal for Nature Conservation.

Over 80,000 animal bones coming from 25 Maya trash mounds connected ancient hunting to fauna abundance. The bones ranged from big, symbolic species like jaguars and Virginia deer to armadillos, rodents and rabbits. Big game was most abundant from A.D. 600 to 900, when the Maya population was at its peak, but during the New Empire, A.D. 900 to the Spanish conquest, large mammals were scarce, especially at the most politically and demographically important Maya cities.

"A depression in large-game availability was caused by the demands of too many people and too many elites. The change in hunting habits was likely prompted by deforestation and a drier climate, which shook faith in Maya rulers' ability to provide 'agricultural abundance'," said author Kitty Emery, an archaeologist at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

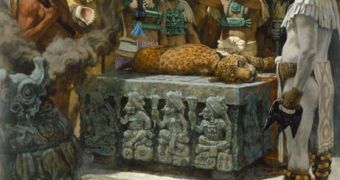

Rulers used to kill large mammals for food, offerings, and as a sign of power and status (through meat, skins and teeth).

"Notably, the changes in hunting practices ran counter to the largely sustainable Maya conservation practices throughout their long history. Even as the ancient Maya lived in large cities over thousands of years, they never exploited game animals to extinction or even local decimation. The large elite class demanded more and more big game in an attempt to prove their status regardless of the worsening conditions. But this scenario is speculative," said Emery.

"The findings show that human-environment interactions are very complex and that simplistic overexploitation models do not provide the answers for the [Maya's later] abandonment of the southern lowlands [of Mexico, Belize, and Guatemala]," said Daniela Triadan, a Maya archaeologist at the University of Arizona.

Triadan signals the rapid rates of species disappearance in Guatemala's southern Pet?n region, an issue aggravated by Guatemala's civil war that lasted till 1996.

"Studying how the ancient Maya more or less kept the ecological balance, despite massive deforestation and alterations of the landscape, may provide vital clues into how to manage these fragile environments today." added Triadan.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //