A group of investigators at the Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington DC announces the development of a new, simple blood test, which is capable of predicting whether or not an apparently healthy person will go on to develop a form of neurodegenerative dementia called Alzheimer's Disease later on in life.

Given the high costs associated with this disorder, as well as its growing incidence in the general population, any early-detection method is bound to have tremendous economic benefits for already-embattled healthcare systems around the world. The new test is capable of discovering Alzheimer's up to three years before the disease sets in.

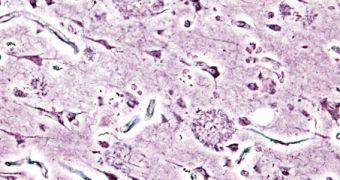

Patients usually have a life expectancy following diagnosis of around 7 years, with just three percent of affected individuals surviving to the 14-year mark. At first, the main symptom is short-term memory loss, which then evolves into mood swings, irritability, aggression, confusion, long-term memory loss, and language impediments, usually accompanied by withdrawal from society.

Death usually stems from a gradual loss of bodily functions. However, researchers have recently found that each step in the evolution of Alzheimer's is accompanied by biomarkers that can be detected well in advance. The new predictive diagnosis method developed at GUMC is just the latest in a long series of blood tests meant to take advantage of that, Nature News reports.

The investigation was conducted on a test group of 525 seniors, all of them over the age of 70. Oxford experts identified no less than 10 lipid metabolites in their blood plasma. These molecules display a degree of accuracy of up to 90 percent when it comes to pinpointing who will go on to develop dementia. This means that doctors will in the near future be able to start treatment right away.

“These findings are potentially very exciting. [However], the findings need to be confirmed in independent and larger studies,” comments University of Oxford neuroscientist Simon Lovestone, who coordinates an important European public-private partnership focused on identifying Alzheimer's biomarkers.

In the study, only 28 test subjects went on to develop symptoms indicative of dementia during the research period. This highlights the need for a much larger, more statistically-relevant investigation. More data needs to be collected on the biomarkers used for this study as well.

“We don’t really know the source of the ten molecules, though we know they are generally present in cell membranes. We also have to look at different age groups and a more diverse racial mix, and we need longer study periods,” says GUMC neurologist Howard Federoff, the leader of the research.

The study is detailed in a paper published in the March 9 issue of the top journal Nature Medicine.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //