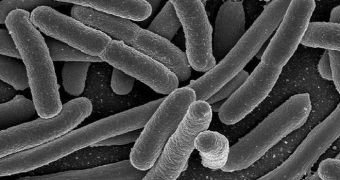

Microorganisms such as bacteria may be capable of forming the same type of social structures as seen in animal and plant species. The amazing conclusion belongs to a new study by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), in Cambridge.

The study largely focuses on aggression, which is an integrated part of the societies. What experts found was that competition did not exist only between individual bacterial cells, but also between small bacterial colonies occupying the same ecosystem.

Furthermore, scientists have discovered that a group of closely-related bacteria can, for example, produce a series of chemical compounds capable of destroying other microorganisms of the same type, while leaving the original group unscathed.

Some bacterial groups preferred slowing down the growth of their rivals, and avoided killing them, the team discovered. Details of the work are published in the September 7 issue of the top journal Science.

Up until now, biologists largely regarded each bacterium as a unique, selfish entity, unable to cooperate and play well with others. Now, a different image is beginning to take shape, where bacteria in a habitat do not play the same social role.

Working with colleagues at the French Research Institute for Exploitation of the Sea, and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI), in Massachusetts, the MIT team focused on studying bacteria from the wild, in order to determine whether any population-level organization existed or not.

“Bacteria typically have been considered purely selfish organisms and bacterial populations as groups of clones,” says MIT theoretical biologist, Otto Cordero, also the lead researcher on the new paper.

“This result contrasts with what we know about animal and plant populations, in which individuals can divide labors, perform different complementary roles and act synergistically,” he goes on to say.

During the investigation, it was clearly established that certain bacterial populations use antibiotics to destroy other groups of microorganisms, especially when competing to occupy the same habitat. This is the equivalent of human groups using chemical warfare on each other.

“In these populations, a few individuals produced antibiotics to which closely related individuals in the population were resistant, whereas individuals in other populations were sensitive,” Cordero explains.

“Those individuals that don't produce antibiotics can benefit from association with the producers, because they are resistant. In other words, antibiotics have a social effect, because they can benefit the population as a whole,” he concludes.

The new research was founded by the US National Science Foundation (NSF).

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //