Since a massive earthquake struck Japan on March 11, the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant has been under a state of emergency, given the amount of damage it suffered. That damage led directly to the release of radioactive particles in the Pacific Ocean, and experts now analyze the consequences.

From the get-go, their work was made very difficult by the fact that authorities in Japan constantly underestimated the severity of the disaster, and showed themselves overly-optimistic that everything will be brought under control soon.

However, the fact remains that the Fukushima accident was rated as a level 7 nuclear disaster, which means it's comparable only to the Soviet Union's Chernobyl event in magnitude and damage.

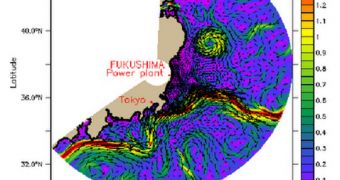

On the other hand, unlike Chernobyl, the new event caused massive damage to the nearby ocean. Significant amounts of iodine, cesium and other radioisotopes now pollute the waters.

“When it comes to the oceans […], the impact of Fukushima exceeds Chernobyl,” explains Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution (WHOI) chemical oceanographer Ken Buesseler. The datasets the expert has access to are extensive.

Readings were collected from the water discharge canals found all around the power plant, from coastal water south of the facility, and from as much as 30 kilometers offshore.

“Levels of some radionuclides are at least an order of magnitude higher than the highest levels in 1986 in the Baltic and Black Seas, the two ocean water bodies closest to Chernobyl,” Buesseler explains.

The investigator was able to conduct his research with funds provided through a rapid-response grant from the US National Science Foundation's (NSF) Division of Ocean Sciences (DOS). His study is meant to establish baseline concentrations of several radionuclides in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans.

“Finding this information early on is key to understanding the severity of the releases and related public health issues,” the investigator reveals. “After Chernobyl, fallout was measured not only in samples close to the site, such as those in the Black Sea, but as far afield as the north Pacific Ocean,” he adds.

“Like the people of Japan--though certainly to a lesser degree – we are dealing with a radiochemical situation that will be with us for a long time,” explains the director of the NSF chemical oceanography program, Don Rice.

“To understand how the ocean and atmosphere have handled this contamination in the years ahead, we must first get a snap-shot of the situation today. Buesseler and [chemical oceanographer Henrieta] Dulaiova are doing just that,” the NSF official concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //