Throughout North America, a host of unusual temperature fluctuations has had experts wondering as to why snow falls in the Deep South regions of the United States, while the northern parts of the country, and southern Canada, are hotter than regular. A large-scale atmospheric pattern may be to blame.

Climate scientists believe that the climate pattern known as the Arctic Oscillation (AO) is what causes the overall configuration of warmer-than-normal temperatures in the northern parts of the continent, and cooler-than-normal temperatures in the south.

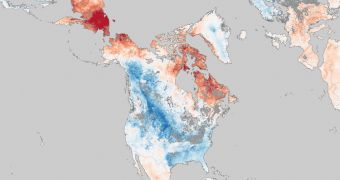

In the attached image, experts at the NASA Earth Observatory listed all temperature anomalies that were recorded in January 2011, by comparison with a years-long average for the same are.

“Because this image shows temperature anomalies rather than absolute temperatures, red or orange areas are not necessarily warmer than blue areas. The reds and blues indicate local temperatures that are warmer or colder than the norm for that particular area,” EO experts write.

Some of the most interesting things that happened this winter include snowfall in the Deep South, snowstorms battering the East Coast, as well as a new record for low temperatures – minus 43 degrees Celsius for International Falls, Minnesota.

At the other end of the spectrum, areas in the northern US and southern Canada were subjected to temperatures that were considerably higher than normal. NASA experts kept track of the anomalies via their orbital capabilities.

The land surface temperatures was recorded using the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instrument on the space agency's Aqua satellite. In the map, January 2011 temperatures are compared to average ones taken between 2003 and 2010.

“The AO is a pattern of differences in air pressure between the Arctic and mid-latitudes. When the AO is in 'positive' phase, air pressure over the Arctic is low, pressure over the mid-latitudes is high, and prevailing winds confine extremely cold air to the Arctic,” EO experts reveal.

“But when the AO is in 'negative' phase, the pressure gradient weakens. The air pressure over the Arctic is not quite so low, and air pressure at mid-latitudes is not as high. In this negative phase, the AO enables Arctic air to slide south and warm air to slip north,” they add.

According to new data inferred from US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) forecasts, it would appear that the AO could become positive again by the start of February. However, there is no way of knowing for sure whether that will actually happen.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //