According to investigators at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, the brains of people who are placed under anesthesia tend to exhibit the same type of response to external stimuli as the brains of individuals in deep sleep. If this turns out to be true, a direct consequence would be the fact that experts would develop a new theory of consciousness, from which a new type of test for detecting and analyzing the loss of consciousness could be derived. Such an investigation method could be applied, for example, on coma patients, PhysOrg reports.

Details of the new research appear in the latest issue of the respected journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS). The SMPH team was led by neurology expert Fabio Ferrarelli, who determined that the investigation should be focused on the “conscious sedation” anesthetic midazolam. This substance is regularly given to hospital patients before undergoing such relatively minor procedures as colonoscopies. For the study, the drug was administered to volunteers.

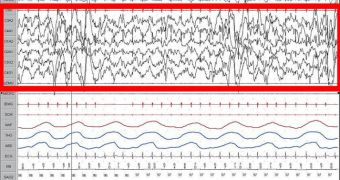

The investigators then wired the participants to electroencephalography (EEG) machines. While the instruments were recording, they then applied a noninvasive technique known as transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) to the cortical neurons of the scalp. EEG was used to determine the extent and nature of the effect that was elicited once TMS was applied. The researchers discovered patterns of brain activity that were very similar to the ones exhibited by the brains of people in deep, non-rapid eye movement (non-REM) sleep. This is another instance in which consciousness is known to fade.

“Based on a theory about how consciousness is generated, we expect to see a response that is both integrated and differentiated when the brain is conscious. When there is a loss of consciousness, either due to sleep or anesthesia, the response is radically different. We see a stereotyped burst of activity that remains localized and fades quickly,” UW Professor of Psychiatry Giulio Tononi, who is also a consciousness expert and a coauthor of the PNAS paper, explains.

“The idea that some anesthetics 'hijack' the natural sleep-promoting centers was proposed recently by others. While our present findings do not directly confirm this hypothesis, they are consistent with a set of shared mechanisms. That is, that the loss of functional connectivity between brain regions is a characteristic that sleep and anesthesia share, and that we think might be causal in the loss of consciousness in both cases,” another study coauthor, Dr. Robert Pearce, adds. He is the SMPH chair and professor of anesthesiology. “We want to know whether a person is really there, and to us, it is important that the method is grounded on a theoretical model of what is required for consciousness,” Tononi concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //