A team of experts at the Arizona State University (ASU) and the University of Colorado in Denver (UCD) say that ancient hominins who lived during the last Ice Age were biologically and mentally capable of adapting to the new conditions brought forward by climate change.

Investigators conducted the new research by creating a series of complex, computerized simulations of the conditions that our ancestors were exposed too. The data they obtained in this manner were also used to figure out how Neanderthals reacted to the same conditions.

The models are far-reaching, in the sense that they cover multiple hominin groups. The goal was to gain a comprehensive picture of how the last Ice Age influences our ancestors, regardless of species.

How Homo sapiens won the battle against Neanderthals, some 35,000 to 30,000 years ago largely remains a mystery to this day, but many researchers seem to believe that climate change had a hand in selecting the winner.

Full details of the new research will be published in the December print issue of the esteemed scientific journal Human Ecology. The data were also published in the November 17 online edition.

“To better understand human ecology, and especially how human culture and biology co-evolved among hunter-gatherers in the Late Pleistocene of Western Eurasia (ca. 128,000-11,500 years ago) we designed theoretical and methodological frameworks that incorporated feedback across three evolutionary systems: biological, cultural and environmental,” Michael Barton explains.

“One scientifically interesting result of this research, which studied culturally and environmentally driven changes in land-use behaviors, is that it shows how Neanderthals could have disappeared not because they were somehow less fit than all other hominins who existed during the last glaciation, but because they were as behaviorally sophisticated as modern humans,” he adds.

Barton, who is based at ASU, is a renowned authority and a pioneer applying computer modeling to archaeological findings. This is a relatively new area of science, says the expert. He was also the lead author of the new study.

The models revealed that Neanderthals were just as adaptable to their changing environments as modern Homo sapiens were. Until now, it was thought that the other species was out-competed evolutionarily by our own.

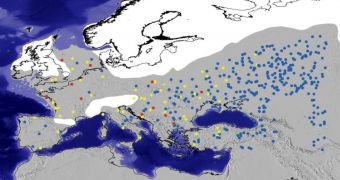

Archaeological data included in the models covered a period of about 100,000 years, and tracked the development of humans throughout the Western parts of Eurasia. This is where most relics from that long-gone time were found.

Regardless of species, our ancestors spread out widely during the Ice Age, trying to find as much food as possible in the changing climate. They were therefore equally motivated to evolve, although some populations were more adaptive than others.

What the research suggests is that Homo sapiens mingled with the Neanderthals to such an extent that the latter became unrecognizable as a distinct population. This outcome shows that Neanderthals were equally capable of adapting to changes as any other hominin species.

Funds required for this study were provided by the US National Science Foundation (NSF), a Fulbright Senior Research Fellowship and a Fulbright Graduate Student Fellowship.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //