Not long after the Moon formed around Earth, a giant impactor, most likely a meteorite or large asteroid slammed into its southern hemisphere, creating the most massive crater on the surface of the natural satellite. The South Pole-Aitken basin has been determined to be no less than 1,500 miles in diameter, and has an estimated depth of about five miles. At this point, it provides experts with a view into how the early Moon may have looked like. Scientists say that studies of the basin will most likely go on for many years to come, Space Fellowship reports.

“This is the biggest, deepest crater on the Moon – an abyss that could engulf the United States from the East Coast through Texas,” reveals NASA Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC) expert Noah Petro. It is estimated at this point that the impact was so powerful that it scattered material from the lunar crust all over its surface, as well as far into outer space. The impactor simply plowed through layers of the crust, exposing what geologists believe to be the first layers that formed once the Moon coalesced. It is also believed that the strength of the impact liquefied the bottom of the crater, producing an apocalyptic sea of red-hot molten rock.

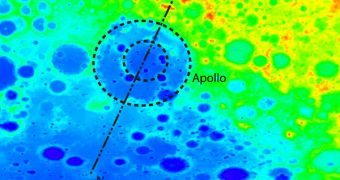

But this was just the messenger of things to come. Over the next few billion years, the Moon was continuously battered by comets, asteroids and meteorites of various shapes and sizes, which poke marked its surface with crater, debris and solidified lava. The Bombardment was so intense that glimpses of the original lunar crust are very rare. However, views into the deep, original crust are rarer still, and so the southern basin is tremendously helpful for studies aimed at figuring out how the Moon formed. In addition to the large depression, the 300-mile wide Apollo crater, located nearby, also provides a view into the Moon's past.

“It’s like going into your basement and digging a deeper hole. We believe the central part of the Apollo Basin may expose a portion of the Moon’s lower crust. If correct, this may be one of just a few places on the Moon where we have a view into the deep lunar crust, because it’s not covered by volcanic material as many other such deep areas are. Just as geologists can reconstruct Earth’s history by analyzing a cross-section of rock layers exposed by a canyon or a road cut, we can begin to understand the early lunar history by studying what’s being revealed in Apollo,” Petro said on March 4, at the Lunar and Planetary Science meeting, held in Houston, Texas.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //