Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), led by biologist Jeroen Saeij, are now hard at work, analyzing the differences in toxicity between various Toxoplasma gondii strains. The work could help save thousands of lives yearly.

Toxoplasma, as a parasitic microorganism, infects no less than 33 percent of the global population, but only some of its strains are extremely harmful to humans. Others cause no discernible effects whatsoever, and experts now want to learn what's causing these significantly-different results.

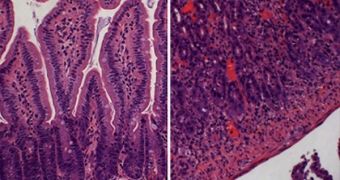

When the parasite is harming its host, one of the most common symptoms is encephalitis, which can be extremely dangerous. The condition is characterized by the inflammation of the brain, which results in headache, fever, confusion, drowsiness, and fatigue.

Seizures, convulsions, tremors, hallucinations, and memory problems may also develop if the condition is not addressed. But Saeij learned that two of three most common strains of Toxoplasma tended to literally take care of their hosts.

These strains produced a protein that played a direct role in preventing brain inflammation. The third however did not produce the molecule. The new study could help experts treat people with Toxoplasma infections, but also those suffering from Crohn's disease and other forms of brain inflammation.

Saeij was the author of a new paper describing the findings, which was published in the June 15 issue of the scientific journal Cell Host & Microbe. MIT postdoctoral researcher Kirk Jensen was the lead author of the paper.

“There’s a lot of these inflammatory diseases, and if there’s a general pathway that’s really good at quelling inflammation, there might be [drug] applications,” adds the team leader, who also holds an appointment as an assistant professor of biology at the Institute.

“What the paper shows really well is that you have these different strains and even though they are quite similar, each type is adapted to different host environments,” adds University of Pittsburgh assistant professor of biological sciences Jon Boyle, who was not a part of the study.

The ROP16 protein was identified as the main player in averting brain inflammation. Researchers with the MIT team will soon embark on a new scientific quest, which will seek to bring this molecule to the market in the form of an efficient therapy.

But Saeij says that this is not that simple to achieve in practice. “In reality, going from a discovery to a drug can take decades. You hope that you contribute to something like that, but that’s always a long road,” the team leader concludes.

14 DAY TRIAL //

14 DAY TRIAL //